One Gītā Śloka to Live One’s Entire Life By

[Published in the Arsha Vidya Gurukulam 34th Anniversary Souvenir, 2020]

If you want to have one verse for your entire life, you have to look for verses from the seventh chapter because beginning with the seventh chapter alone Īśvara is discussed. There are interesting verses before the seventh chapter, but you have to bring Īśvara through the back door. The first six chapters predominantly talk about you, tvam pada, what you can do as an individual. It is all from the standpoint of the individual, so we have to combine verses. The verses must have all the elements that we require. This verse is something in which we can find all the things that we want.

“Mokṣa” is a word. The root is muc, meaning bandha-nivṛttau, removal of bondage. The dhātu is used, the word “mokṣa” is formed, and the meaning is freedom from bondage. What is bondage? What you do not like and do not want is bondage. If you want to be here and you cannot be, then it is bondage. You are within the walls of a prison. If you are what you do not want to be, that is bondage. It is a well-discussed topic. There is an expression, “I do not want to be a saṁsārin.” Saṁsāra means I am sometimes happy, sometimes unhappy, always struggling to be somebody, struggling for self-approval. I don’t have it, and therefore I want approval from others. Even if approval comes from others with some reservations, I still have to approve of that. I have no self-approval, which is why I require others’ approval. Even with that, my original problem of lacking self-approval will remain the same. What is required is self-approval, and the self cannot be approved by the self unless it is approvable.

The one who disapproves of the self has to discover that the self is approvable. The self is approvable because it cannot be made any better. In terms of time and longevity, it cannot be made better. It should be free from the fear of change and aging. In other words, the self must not be subject to time. The self is totally approvable. In terms of adequacy, the self must be one that cannot be improved upon. In other words, it should be the whole. The whole is me, which cannot be improved upon. If this is so, then there should not be anything other than myself. Wholeness implies that everything is also me.

Many areas have to be covered. If that is the truth, how am I going to know the limitless with my limited mind? I need not know at all because I am limitless. That I have limitation is the problem; that I need enlightenment is the problem. We need to address a non-existent problem. I have to make you see that the problem does not exist.

Mokṣa is freedom from saṁsāra. Saṁsāra is the need for self-approval, the feeling of being small and insignificant. The self is not small or insignificant, therefore there is no problem. The only problem is that one does not see or

know it, or one sees and knows it wrongly. If you commit a mistake regarding the limitless, then you are limited. Then you can say, “I am a little less limited than you are.” But when you are talking in terms of the limitless, what is the distance between the limited and the limitless? Whether you have more or less, it is infinite. Between one and infinity, the difference is infinity. Among the limited, you can say that one has more or less. But in the limitless, there is nothing more or less.

Among the limited, you find there can always be comparison. Between the limited and the limitless, however, the difference is always infinite. If one knows, there is truth; if one does not know, the saṁsāra loss is infinite.

&न्ब्स्प्;इह चेदवेदीदथ सत्यमस्ति न चेदिहावेदीन्महती विनष्टिः ।

भूतेषु भूतेषु विचित्य धीराः प्रेत्यास्माल्लोकादमृता भवन्ति ॥ ५ ॥

iha cedavedīdatha satyamasti na cedihāvedīnmahatī vinaṣṭiḥ |

bhūteṣu bhūteṣu vicitya dhīrāḥ pretyāsmāllokādamṛtā bhavanti || Kenopaniṣad 2:5 ||

Therefore, if you are the limitless, free from limitation, and that is what you really want. Behind every basic want is this want: everybody wants to be free from being limited. If there is such a thing as limitless, can it be separate from you? If you are not included in or are different from the limitless, then what is the limitless? If I am not the limitless, and the limitless is not me, then naturally I limit the limitless and the limitless limits me. Therefore both are limited. This is pure logic. The limited is also denied, separated from the limitless.

If there is such a thing as limitless, it has to be me. The “me,” whatever you say you are, has to be examined. It is a point of view. Nobody says that your body is limitless. It is bound by time, aging, and it will die. If that is you then there is no mokṣa, freedom. Then you have to deal with existential issues—how to make the most out of the limited that you have and live your life. That is life. The idea that the body is ‘I am’ is only a point of view.

Whether you are this body-mind-sense complex is something to be examined. It was never examined, and there is also no way of examining unless you have a means of knowing. The Gītā tells me that what is construed to be me, the self, the “I,” is not totally true. If the body-mind-sense complex is taken to be you, there is some reason for it. If you look at the east and see the sunrise, that perception is true. There is a blue sky that looks like a ceiling, this perception is true. The stars do not appear during the day, this perception is true. What is the conclusion? It is that the sun rises in the morning and travels to the west. The conclusion “I see, therefore it is true” is not a valid conclusion, however. In an exam, it will result in zero marks. So you cannot conclude that because you see, your perception is true. You have to do vicāra, you have to inquire into it. You have to take certain other perceptions into account as well. In the summer, in Norway, you see the sun rising all over. There is no east or west because you are by the North Pole. Night comes and lasts for five minutes. There is a midnight sun. The rising sun is a perception, and this is also a perception. How are you going to reconcile these perceptions? You have to think. You come up with a different conclusion, which is jñānam. That conclusion is that the sun does not rise or set. The observer is standing on the earth, which is moving on its own axis and going around the sun. That is called knowledge. Perception is one thing, and knowledge is quite another.

“Swamiji, my experience is that if my new shoes bite my toes, I don’t say that in one remote corner of my body there is hurt. That is not the experience. The experience is that I am pinched. When the body gathers a couple of extra kilos, my experience is that I am bigger than before, not that the body is bigger than before.” If you say the body is bigger than before, you will have no complexes. The body is free of complexes, which is why it keeps on gathering and storing fat. If I am separate from the body, then I am also free of complexes.

Who is in-between in this complex situation? It is a point of view. Then what is the view? The view has to be clear. If the view is clear, it is called mokṣa, freedom from becoming; not only now, but later also. Later is also now. Now is the reality. Now I am free. That is called freedom, mokṣa. Suppose I can make a monkey develop a complex by saying, “You are in the ladder of evolution. You need to evolve into a human being.” If it understands this, then it has already become a human being because it will get all the complexes. Poor monkey! It is better to be either a monkey or enlightened, if there is such a word as “enlightened.” It’s better not to be confused, this being in-between is a nuisance. Just be a monkey and lead your life in the treetops with your family. But if you are a human being, then go all the way because you are aware of yourself. It’s better to be aware all the way. This half-knowledge is dangerous. That is what the problem is. Everyone wants to be free. Free from what? If a little examination is there, then one is free from saṁsāra, life as a becoming person. ‘Becoming’ means a time-bound person. That is what the verse talks about.

Jarāmaraṇa mokṣāya, the purpose is to gain freedom from the basic problem of change. You are sometimes happy, sukhī, and sometimes unhappy, duḥkhī. The whole life is this, one state alternating with the other. This is called saṁsāra, characterized by time, change, old age, etc. If your conclusion is that you are old, then you are going to die, being bound by time, jarā, old age, and maraṇa, death. Death is upalakṣaṇa, it stands for the time-bound nature of all types of becoming life, being reborn and suffering the same again. If that is the truth, then you will not struggle against it. There is an untaught, natural struggle to be someone who is free from this. You need to accept that there is no escaping from jarā and maraṇa; they stand for every form of change. All fear is because of change. Therefore, there is only one thing that can make you free from time, change, and being small and inadequate. This is that the self you are must be already free from time, change, and being small. In fact, nothing should be away from it. Everything should be the self.

We have a culture based upon this fact, which is known and knowable. There is a tradition of teaching, and that culture is going to be different. Mokṣa has nothing to do with salvation. It is owning up what is true, knowing what is true about yourself. This is mokṣa. Mokṣāya yatanti, yatnaṁ kurvanti, those who are committed to gain this mokṣa, those who are aware of the issues involved in human life, and who have come to understand that it is a pursuit of knowledge, those people make proper effort. There are two verbs in the verse. The first line has the verb yatanti, making effort. The sentence is, ye yatanti te viduḥ, those who make effort gain all that. We are working on yatanti, those who seek mokṣa, freedom from a becoming life, from a sense of bondage. “I am small” is the usual knowledge of every individual. “I am limited, wanting and a mortal.”

This is true and it is not true. The body is mortal, there is no denying that. To say, “I am mortal,” the body must be saying it or I, the one who owns this body, must be saying it. The body does not say, “I am a mortal.” It has no complexes or fear. The problem is the person who looks at himself from the standpoint of the body. It is not a point of view for the person, because to look at oneself through one’s body one has to know what the self is. If one knows, then one can say, “I am a mortal” like an actor appearing in a drama. The actor speaks as the character that he

assumes in the play, saying that he is a king or a minister, etc. He knows he is not any of them, but these characters are centered on him. Therefore the role is me, but I am not the role. That is the truth.

Jarā, old age and maraṇa, death—what dies, dies and what ages, ages. If the person survives, then the body is like new clothes. When these wear out, he wears new clothes again; the one who indwells in the body takes new bodies. This is the saṁsāra-cakra, cycle of becoming. This is a cycle, and it will go on as long as one thinks that “I am born, subject to time, grow, metamorphose to become an adult, decline and die with reference to one body and again the same process.”

This is called saṁsāra. There is no nivṛtti, cessation, for this if the self is like the individual, limited. In the vision of the Gītā, the self is free from time, birth, and death. Birth and death are discussed in the sense of upalakṣaṇa, meaning they are used to point out the struggle to be different from what I am. I necessarily make a judgment about myself, and in it, I see myself as not being everything I want to be. Therefore, I want to be different. If I am really limited and wanting, I will be struggling forever. Dissatisfaction leading to disapproval of myself is there because I am self-judging.

This is called saṁsāra. Mokṣa is freedom from this struggle. You struggle not to struggle, you seek not to seek, but then you find yourself doing the same thing over and over again. As a child, a young adult, an adult, you struggle. When you have reached a certain age, you still struggle. Seeking is not for the sake of seeking; it is meant for finding a destination. Without having a destination, it is all half-way. That is why discovering the self, if that is true, cannot be improved upon because it is the total, the whole. In one word, pūrṇaḥ ātmā; it is brahma, the limitless.

Mokṣa requires puruṣārtha-niścaya, a certain clarity about what you want basically. This is the beginning and this is the end. Artha means what you want; puruṣārtha is what is wanted by all people; puruṣaiḥ sarvaiḥ arthyate, what is desired by all persons. One person wants to sell and the other wants to buy and the third brings them together—three different intentions. People seek different things. Behind all the selling and buying, they are all seeking a certain satisfaction. If you look over the shoulders of varieties of things that you seek, you find a common goal—freedom from struggle, mokṣa. There are many puruṣārthas. People want artha: money, real estate, name, fame, and power. Then any ego satisfaction is kāma. It looks like artha but it is kāma, seeking artha for satisfaction, an ego trip. People seek pleasure, satisfaction called kāma, and then they seek artha, wealth and so on. Then dharma: they invest for their future life by earning puṇya, because they accept that there is no end to this journey and they are planning for the next birth. Just as they plan for retirement, they plan for the next birth also. Earning puṇya is called dharma. Self-growth is also dharma. That also gives you a better self-image, satisfaction, and helps you to achieve your potential. You do not underachieve.

All these are the puruṣārthas. You can seek them all—artha kāma and dharma—but you must have clarity and finally you must know what you want. And you need to know now, not after retirement. It is like doing course work while having a PhD in view. Before the PhD, you have to get the credits— undergraduate, graduate. There is a long way to go. The process is there. Similarly, even though you seek artha, kāma, dharma, the goal of mokṣa is clear as you pursue them. In this way, marriage becomes a means and parenting also becomes a means. Anything you do becomes a means. Mokṣa is fixed as the end to be accomplished. This takes a lot of thinking and opportunities. Not everybody gets a chance. Nobody thinks he can be the whole. It is a long way.

People come to these camps not for mokṣa but to listen to Gītā, to do something spiritual or to learn something to do daily. They have different motivations, but after coming here and listening, things slowly change. First you come for a break from your job, a holiday, and then you learn. People come for different things but they all get some clarity because we talk about the puruṣārtha. Later you become clear about what you want, and that clarity is called vyavasāya. If you know ‘the thing’ in life to be achieved, there is a settled pursuit. If that is not clear, then the choices are endless. It is like a child, an eight-year-old, taken to a toy shop. The child is told to choose a toy. It is confusing; what will he choose? He wants to have it all. Finally, he picks up one after thinking. Every toy is obsolete after ten minutes. The child will always feel, “I should have chosen another.” This is unnecessary guilt. We should save the child from this by buying one toy and then giving it.

In life, we are asked to choose. There are endless things in front of us. In Western culture, tastes and choices are fanned from childhood. For Indians, it is all total acceptance—when coffee is offered, whoever is serving decides how it should be and gives it to you. They will not ask you how you would like it. It is a different culture, one in which yadṛcchayā lābha santuṣṭāḥ, one is satisfied with whatever life has to offer, to unfold. This is a different attitude. You believe in something big. So having this clarity in what you need to achieve, you have vyavasāyātmikā buddhiḥ. Every other pursuit subserves that pursuit. Once that is settled, then you convert your day-to-day life into a means to achieve that. Life is yoga only when the clarity, vyavasāya, is there. Marriage, parenting, job, accomplishments, everything becomes yoga.

An ambition is also a desire. What is the difference between an ambition and desire? An ambition is achieved by fulfilling many small goals in stages. That is why life is divided into stages, called āśrama—brahmacarya, gārhastya, vānaprastha, sannyāsa. Everyone has to grow into sannyāsa. Whether one is a sannyāsī or not one has to grow into it. The goal of a sannyāsī is clear—mokṣa. The goal of a non-sannyāsī, one who has clarity, is the same. lokesmin dvividhā niṣṭhā purā proktā mayānagha jñānayogena sāṅkhyānāṁ karmayogena yoginām “O sinless one, the two-fold committed life-style in this world, was told by me in the beginning—the pursuit for knowledge for the renunciates and the pursuit of action for those who pursue activity.” (Bhagavad Gītā, 3.3)

Asmin loke, in this world, there are dvividhā niṣṭhā, two lifestyles. The Sanskrit root sthā means to stay; nitarāṁ sthitiḥ iti niṣṭhā. It means staying in a form, you live your life in a form. This is called niṣṭhā, a lifestyle for mokṣa. Then only there is a discussion. Vyavasāyātmikā buddhiḥ, there is only one thing, clarity must be there. The more informed you are, the more choices disappear and options become fewer. The less informed people have more choices. The more you know, there is no option. Do you want to be happy or unhappy—where is the option? The more you know, the more clarity there is. That is why vyavasāya is important. Mokṣa is in the form of knowledge. Either you are free or you can never be. If you are free, you have to know. Therefore, yatanti, effort. First puruṣārtha niścaya is there, afterwards yatanti.

There are two committed lifestyles, dvividhā niṣṭhā. Karmayogena yogināṁ jñānayogena sāṅkhyānām, sannyāsinām. You can be a sannyāsī because you want mokṣa. For that, you have to get whatever life, marriage, and parenting can give. If you want to jump the queue, straight away take sannyāsa, and then get mokṣa, then you need to have a mind that is contemplative. Sannyāsa is characterized by a total absence of competition, no personal agenda, and pursuing knowledge exclusively. This is the jñāna-yoga-niṣṭhā, the exclusive pursuit of knowledge. A sannyāsī is one who has no other duty. He has ritually absolved himself from all duties—familial, social, national, and devatā—to pursue exclusively the knowledge of what “is.” It is a pursuit of knowledge of Īśvara. In Indian society, there is a place for this pursuit. He is a sādhu because that is the fourth āśrama.

You can take to a life of a sannyāsī characterized by the pursuit of knowledge. Lord Krishna says, jñānayogena niṣṭhā mayā prokta, this sannyasināṁ niṣṭhā, exclusive pursuit of knowledge by sannyāsīs, was already told by me. The other choice is karma yoga. This is the lifestyle of yogis, those who have that clarity and want to have mokṣa. Their commitment to life is characterized by karma-yoga. There is no separate bhakti- yoga, etc. Bhakti is common to both lifestyles. A sannyāsī has to have bhakti, and a karma-yogī is also a bhakta. If you do pūjā, it is kāyikaṁ-karma, physical karma, recitation is vācikaṁ-karma, karma using speech, and meditation is mānasaṁ-karma, karma using the mind. There is no separate bhakti.

Bhakti is relating to Īśvara, bringing Īśvara into your life. Do you bring Īśvara into your life, or is Īśvara already in your life and you acknowledge his existence? We can say it both ways. If Īśvara is already there, then you have to know. By knowing, you bring Īśvara into your life. If all that is here is Īśvara, then you had better know. If you know, then there is so much Īśvara in your life. Relating to Īśvara is śraddhā, bhakti. A sannyāsī is a bhakta, a karma-yogī is a bhakta. Bhakti is common, and the pursuit of knowledge is also common.

Knowledge is not negotiable because you are already free. You are not going to become free. You have becoming, that is what you have been doing for so long. You are free. You need to know. That is not negotiable. Exclusively pursuing knowledge implies a certain maturity, certain contemplativeness.

संन्यासस्तु महाबाहो दु:खमाप्तुमयोगत: |

योगयुक्तो मुनिर्ब्रह्म नचिरेणाधिगच्छति || 5:6||

sannyāsas tu mahā-bāho duḥkham āptum ayogataḥ

yoga-yukto munir brahma na chireṇādhigachchhati

“Renunciation of action, O Arjuna, is difficult to accomplish without karma-yoga.

Whereas, one who is capable of reasoning, who is committed to a life of karma-yoga, gains Brahman quickly.”

(Bhagavad Gītā, 5:6)

You live for a length of time and gain a certain order within yourself. Putting the inner house in order is not an ordinary thing. Then whether you take sannyāsa or not, the knowledge has no hindrance. Live a life of karma-yoga. The one who lives a life of karma-yoga, who is a muni, vicāravān puruṣaḥ, one who is capable of reasoning, continues the vicāra. Then only there is karma-yoga. The clarity has to gather more clarity. As you do enquiry, continue the study. This is a study of life, seeing what ‘is’. It is a different type of learning.

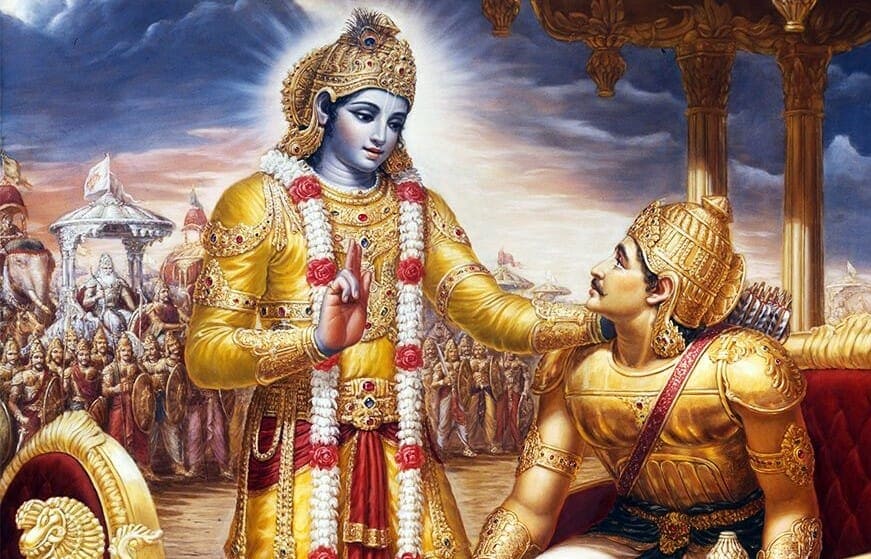

There is no time involved in this. You come to know what Brahman is. Yatanti mām āśritya, they make effort, having taken refuge in me. This is an important sentence. Māṁ, in me, refers to parameśvaram. Krishna is using the first person here as Īśvara. He speaks as the person Krishna only in one or two places in the Gītā. “You are my bhakta, friend,” he says to Arjuna only in one or two places. There Krishna is speaking as the son of Devaki. In all other places, he uses the first person singular to mean the svarūpa or manifest form of Īśvara. This teaching has to

come only from Īśvara. Vyasa presents the teaching through Krishna as Bhagavān. He looks upon Krishna as an avatāra.

The Mahābhārata is the first book to introduce Krishna as Bhagavān, and it also discusses avatāra-vāda. By using the phrase mām āśritya yatanti ye, he is already talking about either a sannyāsī or a karma-yogī. Īśvara is in the life of both of them. Mokṣāya ye yatanti, yatnaṁ kurvanti, those who make efforts, who do what is to be done for gaining mokṣa. Mokṣa is in the form of knowledge. If it is in the form of knowledge, then what is required for knowledge? All that is to be done is covered by the word sādhana, means. Sādhana is a general term, sādhyate anena iti sādhanam, that which is a means for accomplishing something. If you want to talk, your sādhana is the organ of speech. If you want to cook, the sādhana is fire in some form. Pākasya vahnivat, if you want to cook, fire is inevitable. Similarly, jñānaṁ vinā mokṣaḥ na siddhyati, without knowledge, mokṣa does not happen. The primary thing for obtaining knowledge is a means of knowledge. If you want to know the color of an object, seeing is the means.

The object has to be within the range of sight, so either you bring the object into your visual range or you take yourself to the object. This is all karma, secondary. Now suppose I ask you look at me but not see me; you cannot oblige. You will see me even if I tell you not to see me. If you turn your head away, that is an action. The means of seeing is the primary sādhana, which includes you and the mind. These words are within the range of hearing. Even if I speak softly, you will hear me because of the amplifier. In spite of my being within your range of hearing, there is no rule that you will hear every word I speak. You have not gone to sleep, you are awake and listening. But suddenly you do not hear because your mind was not available. A means of knowing, hearing, implies ears and the mind behind it, and you are behind the mind. That is called a means of knowledge. There is no other way. Suppose I say that there is no other way of arriving at the color of an object except by seeing with your eyes. You cannot say that it is fanaticism. When you are not sure whether what you follow is correct, and then you say that this is the only way, it is pure belief.

There are many ways, and you are not sure whether your way will reach there, but to say that this is the only way is a non-verifiable belief. That is fanaticism. But to say that there is no other way of seeing except with your eyes is not fanaticism. It is the way the setup is. Mokṣah na siddhyati jñānaṁ vinā is not fanaticism because we are not gaining mokṣa; we are already muktaḥ, free. The problem of having bondage does not exist for it to be released. The notion is there, which stems from not knowing, and that has to be fixed up. That is jñānam, knowledge, for which a means of knowledge is a must. There is no other way of knowing anything, whether it is myself or God or the truth of the world. You require a means of knowing, either directly or indirectly, depending upon the object of knowledge. The knowledge that we are talking about requires another means of knowledge to gain it.

My eyes and ears are meant to see and hear. Anything I objectify, whether it is inferred or perceived, is the object and I am the subject. The subject is different from the object. The subject has to know that the truth of the subject is a not subject, and the truth of the object is an not object. This means that it is neither subject nor object; it sustains both. The subject is the knower. The subject has to find out that “I am not the subject,” and he has no means of arriving at that. This is what the Veda tells us, but even after being told, it is a problem. To be told that I am not the subject or the object, that they are the same, one truth, you require a means of knowing that is beyond the scope of the means of knowledge which the subject has. The last portion of the Veda talks about this subject matter, and therefore Vedanta is a means of knowledge. Gītā also talks about the same topic, so Gītā is also a means of knowledge.

To gain knowledge that I am the whole, absolute freedom from dissatisfaction, what do you require? First, for knowledge you have to be a knower, so you require an inner infrastructure such as language. If I am communicating in a given language, you must be informed enough to understand that language. Therefore one of the components in the infrastructure is language—the language in which the teaching is done. Suppose the topic is electronics. For that, you require a technical language, and you must have a commitment, preparedness. If you want to study calculus, you should start with simple calculation. You can get educated from the day you start. You must have the motivation, and the other person must have patience. This is the preparedness. You must have certain adhikāratvam, reparation, and from there you can launch. Any discipline of knowledge requires a launching pad. There are some basics, and then there is buildup and progression. For Vedānta, what is the preparation? The preparation is viveka, a capacity to discern. This is the right thinking. You should be able to see the difference between right and wrong thinking because the whole effort is in correcting your wrong thinking. You cannot afford to make mistakes when you are correcting wrong thinking, otherwise you will replace one wrong with another wrong. This is called ‘neo-Vedānta’, ‘enlightenment’. Substituting one wrong thinking with another wrong thinking is not thinking. You must clearly see what is wrong thinking and what is right thinking; one should be able to sift through and see. This viveka is a minimum qualification.

What is going to be taught is that you are the whole. You have more or less a certain satisfaction, dispassion, objectivity, which all depends upon vyavasāyātmikā buddhiḥ, clarity. When clarity is there, you will have everything else—dispassion, objectivity. In the Gītā, there is a sentence yoginaḥ karma kurvanti saṅgaṁ tyaktvā ātma-śuddhaye. (5:11)

For mokṣa, one must have jñānam; for jñānam, one needs teaching. Teaching is for the preparedness in order to gain mokṣa, knowledge:

द्विद्धि प्रणिपातेन परिप्रश्नेन सेवया |

उपदेक्ष्यन्ति ते ज्ञानं ज्ञानिनस्तत्त्वदर्शिन: || 4:34||

tad viddhi praṇipātena paripraśhnena sevayā

upadekṣhyanti te jñānaṁ jñāninas tattva-darśhinaḥ

“Understand that (which is to be known) by prostrating, by asking proper questions, (and) by service.

Those who are wise, who have the vision of the truth, will teach you (this) knowledge.”

(Bhagavad Gītā, 4.34)

What is karma-yoga? Karma-yoga implies a certain minimum understanding. You require teaching to live a life of karma-yoga. Mokṣa is the end, jñānam is what is being gained, and in the process, you gain the knowledge of what ‘is’. You have to reduce subjectivity. Your subjectivity is reduced to the minimum possible. This is the first step. What ‘is’ is one thing and what you make out of it is quite different; that is subjectivity. To be sane is to be objective. To be objective, you must free yourself from being subjective. You need money—objective. Money buys—objective. It is true that money has buying power. But money buys everything—subjective. It buys a book—objective. But can money buy the power to read the book? I am not sure. Money can buy books, but it cannot make you read. Suppose someone gives you money to read, then you will read, but it cannot buy understanding.

Money can buy a house, but cannot make a home. A home means there must be culture, pūjā, prayer, cooking. A microwave oven cannot make a home; that is a ‘frozen’ home. To make a home, cooking should be there, understanding must be there, open honest communication must be there; then there is a home. Likewise, dhanam, money, can be there, but Dhanalakṣmi cannot be there unless you handle money with respect. Money buys certain things and does not buy certain things. It does not buy love, understanding, maturity, compassion, magnanimity, and all the good things that make a human being human. Money can help you gain all that if you know how to make use of it. There is always subjectivity.

An extra value attached to a particular value is adhyāsa, a superimposed value that is not correct. It is not like taking one object for another, or mistaking one person for another person. It is śobana-adhyāsa, meaning you take money as money all right, but you give it more value than it has. Similarly, in a relationship, love becomes an obsession, it becomes control. This is all due to subjectivity. Love is objective, but subjectivity turns it cabana into control. Our concept of love, etc. is highly loaded. Subjectivity is the loading element. You do not know whether it is compassion or you need to be in the seat of giving, sharing, or you need to control someone so the person can look up to you because you have a low self-image. There is so much subjectivity. We cannot find out from the person’s actions. The action may be benign, which is good, but the need underneath is entirely different. It is not compassion.

Reducing subjectivity and increasing objectivity is the means for being the recipient of this knowledge. To be objective is to understand what “is.” Without understanding what “is” in a total way, you cannot be objective; you will end up being subjective. You need to know what “is,” but what you know is that “there are different things and I am different from all of them.” That is subjectivity—the notion that “I am small and insignificant.”

Let us understand what insignificance is: The whole universe consists of moving galaxies, ever expanding, moving away from each other. Galaxies means billions of stars. Every star must have a system of planets. Our sun is one star among the billions of stars in our galaxy, the Milky Way. It has its own satellites going around it. Planets also have their satellites. Things are moving like this. Light that started 12 billion light years away reaches our eyes today, after traveling at 186,000 miles per second. This is the universe that we are in. In this, if you compare the earth with the sun, it is only a small dot; two-thirds is water and one-third land mass. If the whole earth is the size of the head of a pin, then where is the question of you? This is your significance. Knowledge is insignificant on this scale. You cannot even see your physical body, hence the thought, “This is what I am, insignificant.” Your smallness is there, so there is subjectivity. There is fear, insecurity, alienation. You are not small if you are able to see your connection to the whole. But if you do not see the connection, then you are insignificant and small. If there is connection and you see yourself alienated then there is subjectivity. This subjectivity is basic and it accounts for your insecurity and fear. It is the basic thing, and everything else comes later.

To be objective is to understand what “is.” If you know this, then you may discover that you are highly connected. Lord Krishna says, “Those who make right effort, being highly connected to me, mām upāśritya ye yatanti.” Mām āśritya upāśritya ye yatanti te brahma viduḥ. Ye, those who do this; te viduḥ, they know Brahman. That means that to know Brahman, they have to fulfill certain requirements.

That is why the Gītā is both yoga-śāstra and brahma-vidyā. There is a certain effort and will involved, the will to change, to bring about an inner transformation because knowledge is involved. What is the adhikāritvam, preparedness? It is your own capacity to think, at least to point out any irrational conclusion. You should be able to see the irrationality. In a series of arguments, there are some canyons, big and small.

You should be able to see that. In the tradition, we have evolved a method of creating that kind of infrastructure to help the person see the rational aneurysms, the missing links. You are logical for a length of time and then suddenly illogical. By the force of logic that was there before, you jump a canyon. You should be able to see that. This capacity is vicāra-śakti, it is viveka leading to clarity with reference to what you want. That leads you to the śāstra.

Ātmānam adhikṛtya vartamānaṁ tat brahman te viduḥ, they understand that it is in the form of one’s own body-mind-sense complex plus the subject, and transcending the subject. Therefore you can say, “I am Īśvara, Brahman.” A wave can say, “I am ocean.” From the Indian Ocean, a small wave managed to come to the Atlantic Ocean. The Atlantic wave was proud surf, became a breaker, and broke down into a small wave. It was very sad. It saw the Indian Ocean wave was cheerful and so asked,

“Where are you from?”

“I am from India.”

“What makes you so cheerful?”

“Why are you sad?”

“You are a real oriental. Ask a question, and you get a question as an answer. Do you know who I was? I was a big breaker, a huge wave. Now look at me. I want to end my life. I cannot even do that because when I try to go to the beach I get pushed back. I have no friends. You are also being pushed but you do not seem to mind.

You are from India, are you a guru?”

“I am a guru to a disciple.”

“So what is your trip?”

“My trip is not to be sad.”

“Do I do yoga for that?”

“By yoga, you will not be free form sadness. You should know the teaching.”

“What is the teaching?”

“Do you know that you are the ocean?”

“I am not the ocean. I am caused by the ocean. The ocean is in heaven.”

“You are pervaded by the ocean. The whole wave-world is ocean, it is the cause. You are born of ocean, sustained by ocean, and you will resolve into the ocean. Ocean is the truth.”

“This is too much.”

“Ocean remains; me, small wave comes and goes.”

The Indian wave made the Atlantic wave realize its mistake.

The Atlantic wave said,

“I am pervaded by ocean, that is true, but ocean is the total, Īśvara. How can I be Īśvara?”

“I know that I cannot say that you are Īśvara if you are not.

From one standpoint, as a wave you are pervaded by Īśvara, you can pray to Īśvara, the mighty ocean, all-pervasive ocean, but you have to go one more step. For that, you require a teacher for śravaṇa, manana, and nidhidhyāsana. If you analyze who you are, you will see there is no wave without being water. The top, middle, and the whole of wave is water.

The other waves, breakers, surf, and ocean are water. Who are you, Atlantic wave?”

“I am water. I know I can say I am ocean. There is no ocean without being water. There is no wave without being water. The truth is only water. Now I understand!”

Tat brahma te viduḥ. Such people recognize the two levels of reality. One is self-revealing, self-existent; the swami is sitting here because you see me. I become an object of consciousness. I get loaded in your mind as an object of thought, which you objectify. Therefore I become an object of consciousness. The swami becomes evident because you see me. Your body is, because it is evident to you. That your eyes have sight is evident to you. The cognitive thought in your head is evident to you. That you have knowledge and memory is evident to you. Ignorance is evident to you. The world is evident to you through some means of knowledge. In every knowledge, there is consciousness, object-consciousness. Swami-knowledge means swami-consciousness. It becomes evident to you means it becomes an object of consciousness. Everything becomes evident to you, therefore it is true. Do you exist or not? To whom do

you become evident?

“To me, the self.”

“Who is evident to the self?”

“Me, the self.”

“Are you the self?”

“Yes.”

“Self is?”

“Yes.”

“Evident to whom?”

“Myself.”

That means the self is self-evident. The self-evident is Brahman, the svarūpa of Īśvara. When I say that all that is here is Īśvara, it is final. This is the svarūpa of Īśvara and everything else is a manifestation of Īśvara. You can say I am Īśvara but the ‘I’ has to be in the self-revealing, self-evident consciousness, which ‘is’. When you go to sleep, consciousness ‘is’, lighting up the sleep. When you dream, consciousness ‘is’, lighting up the subject-object and when you wake up, consciousness ‘is’, lighting up the subject-object. If there is a twilight zone in which you are neither dreaming nor awake, there also consciousness ‘is’, lighting up the twilight zone. That is Brahman, you. This is what you experience whenever you are happy. That is why happiness is a highly wanted thing, because it is you, the wholeness. In a dynamic way, this wholeness, kṛstnam adhyātmaṁ brahma, Brahman is recognized as the very pratyagātma, the self, as everything else that is connected to this body-mind-sense complex and everything else that is here. We can look at it this way: all the kārakas, factors involved in action—kartā, agent, karma, object, karaṇa, instrument, and so on—are Brahman. Brahman means Īśvara. The kārakas show the division. The food that we eat is Brahman, the digestive system is Brahman, the one who eats is Brahman, what it is eaten for nourishment, life, etc. is Brahman, what is to be gained is Brahman. Brahmārpaṇam, Brahman is the arpaṇam, the means of offering—the mantra, the chant in the ritual; brahmahaviḥ, Brahman is the oblation, what is offered; brahmāgnau, Brahman is the location where it is offered; brahmaṇāhutam, Brahman is the one by whom it is offered; brahmaiva tena gantavyam, Brahman is what is gained; brahmakarmasamādhinā, Brahman is gained by the one who sees everything as rahman. Everything is one; there is no division.

The one who is able to see Brahman in any situation does not miss Brahman. His buddhi is resolved in brahma-darśaṇam, the vision of Brahman All the dualities are Brahman, so there is no duality. Within that vision alone, there is duality. That gives the space for you to be free, to play the roles in life properly, to follow the script. You do not lose anything. You have found the puruṣārtha, mokṣa, here in this life. While you are living here, you accomplish what you want to accomplish. Dead, you travel and come back.

Therefore make use of the opportunity you have, and make your life a process of growing and seeing.