Swami Dayananda Saraswati

Published in the Arsha Vidya Gurukulam 15th Anniversary Souvenir, 2001

The importance and reverence given to the teacher is something unique to the spiritual tradition of Vedānta. This is because for us the spiritual goal or the ultimate end of a human being is knowing oneself and knowing the Lord.

The śāstra tells us that between the individual, the world, and the Lord there is a certain identity or oneness. It informs you that this oneness cannot be separate from you. You are the one who is conscious of the world, and in fact, the world can be defined as anything that you are conscious of. There is nothing that you can say exists of which you are not conscious. Not only is everything you know the world, anything you don’t know, but can know later, is also the world. Further, whatever is known to someone else is the world. In other words, the world consists of these two things: what is known to you and what is not known to you. Even if what is unknown does not become known to you at all, still it is known to you as being unknown—you are aware of your ignorance. What you know and what you don’t know—these two things together constitute what we call the world. The entire world is what is known and what is not known, sarvaṃ jagat viditamavidaṃ yat sarvaṃ tad jagat.

In this world that you are conscious of, there are many things and there are many beings. All of them are objects of your knowledge. Is this world entirely independent of me, the one who is conscious of it as an object, or am I part of the whole? The śāstra says not just that I am included in the whole, but that I am both the subject and the object. I am the conscious knower of the world, and the world is also me. What, then, is the common basis of the knower and known, the subject and object? The subject that objectifies the object cannot know the common basis; the subject can only know the object. Our usual means of knowledge—perception and various forms of inference, take the subject, the knower, for granted and focus on the object. They are not meant to show us the basis, the substratum, that connects the subject and object. Although we know ourselves experientially, we seem to miss our essential nature because the knower is constantly looking outward, as it were. Our usual instruments of knowledge—our body, mind and sense organs—cannot and are not meant to ‘see’ our true nature.

This is because it is you, the subject, who employs various means of knowledge to know an object. Anything known to you is an object—including time, space and everything in the universe of time and space. If there is a common basis, a substratum that includes you and the universe of time and space, you have no way of knowing it through your available means of knowledge. You have to give up for a number of reasons. All of the means of knowledge at your disposal are external to you. That is, they are employed by you, the subject, to know things other than yourself. Secondly, the knowledge gained by these means is the product or discovery of a human being; it is within the realm of what a human being can figure out. As a human being you have the capacity to stumble upon the knowledge of something that can be objectified by your means of knowledge. However, you cannot just happen upon the knowledge that you are the whole. How would you stumble upon this truth? If you are the subject who uses a means of knowledge to know things other than yourself—things which you can objectify through your mind or sense organs—how can you possibly stumble upon the truth of yourself, the subject? You can stumble upon an objectifiable empirical truth. The discovery of penicillin, for instance, was stumbled upon. I would say that was the greatest human discovery because it really has made a difference in people’s lives. Technological discoveries, such as computers and the like, have not really contributed to our quality of life as much as this discovery. They’ve just made life more complex—and a bit floppy, too. But penicillin was an amazing discovery that was made purely by accident. A scientist was culturing a certain strain of bacteria for another experiment. When the bacteria unexpectedly died, he set about to find the cause. He found a fungus formation on the bacteria, and in subsequent experiments with that fungus duplicated the result with other bacterial strains. Then he knew he had stumbled upon something important. We can thank that scientist for enabling us to perform the varieties of surgery that are done today. Or, more correctly, we can thank penicillin. The scientist himself was baffled as to why he would receive praise for the discovery, saying that he was not responsible for the substance that he accidentally happened upon. The substance was simply there. Anyone else, he said, could have discovered the same thing. His humility was based on his appreciation of the fact that any object can be stumbled upon, can be discovered.

What cannot be objectified, however, cannot be stumbled upon. You cannot stumble upon the essence, the common basis, of the subject and object, because you are that very essence. There is no way to stumble upon the knowledge that you are this essence, because it has to come from that very essence, that very source which makes it possible to discover things and to wield all other methods of knowledge. Only the very source of this world, the very source of all knowledge can give this knowledge to us. The body of knowledge which comes from this source is called Vedānta, as it is found in the end part (anta) of the Veda. We look upon it as a means of knowledge. Being a means of knowledge, it is not a matter of belief.

We generally believe that religious scriptures are the products of revelation. The Bible is believed to have been revealed by God and the Gospels, by the Son of God whose words were collected by his disciples. Later the prophet Mohammed said that he was the chosen mouthpiece of God. He said that God talked to him in his dreams and that he compiled God’s words into the verses called the suras that form the Koran. It would seem that God goes on revealing different things to different people at different times. What are we to make of this? Maybe God has different tongues, so that there is one set of truths for one prophet, and another for a different prophet, which is why God revealed different facts to different peoples. Or, maybe different Gods spoke to different prophets? Which truth should I believe; which truth should I not believe? Furthermore, why should I believe any of them when there are so many different versions, none of which can be verified? According to one set of beliefs, if I follow a certain path, I will go to heaven. That requires that, first of all, I have to believe that I will survive after the death of the body. Then, I must believe that heaven exists, and that I will like being there. It is one

continuous set of beliefs, non-verifiable beliefs. You may hold a belief that is non-verifiable, but how can you convert another person to a belief that is non-verifiable? Some beliefs are verifiable, like some systems of medicine. In homeopathy, for instance, there actually is no medicine in the pill that is given as a remedy. According to homeopathy, every disease is due to a gross substance, and the subtle aspect of the same substance will relieve you of the disease. The basis of the treatment is that similar cures are similar. The diagnosis is determined from your symptoms and seemingly irrelevant information, such as your marital status, salary, and so on. Then the doctor will refer to his manual of symptoms and remedies and choose the proper one. He then introduces one drop of the mother tincture into a big bucket of water and goes on stirring it for hours. Then he takes one drop of this diluted substance, puts it in another bucket of clean water, and again stirs it. This procedure is called potentizing the remedy.

A substance is considered highly potentized if it has gone through the process ten times. Finally, a tiny pill is made of a drop of the final substance mixed with sugar water. Although homeopathy may not be understood scientifically, the system often works; it is verifiable. If you say, “Swamiji I don’t believe in it,” you can try it yourself. You can be certain that if your symptoms worsen the next day, the doctor will be very happy because it means he or she has given you the correct medicine. The homeopathic principle is that the cure will, at first, aggravate your malady. According to homeopathic doctors, there is a medicine for every condition. Unlike an unverifiable belief, homeopathy is verifiable. While it may not be a system of medicine, it is a system of cure. Āyurveda also is a system of cure that uses herbal remedies. Although we may not know what part of a particular leaf cures an illness, we know that the leaf does cure. Unlike a system of medicine, which extracts a certain part of a leaf to make a remedy, both Ayurveda and Homeopathy uses the whole leaf. The whole environment remains intact. Even though, in a particular leaf, there may be only one substance that is the actual cure, the other substances in the leaf are considered to be adjuncts, and are not discarded. The medicinal substance in its own natural environment is considered curative in the Ayurvedic and homeopathic systems. At any rate, you can verify your belief in such systems of cure by taking the medicine.

But how are you going to verify your belief that there is a heaven? If you say, “Swamiji, after death we can verify that there is heaven,” then I will have to accompany you there. Even then, if you tell me, “Swamiji, what you said is true. Here we are in heaven,” that is not verification. You have to verify it here. If I were to tell you, “Yesterday I went to heaven and came back. There is a heaven,” that statement would require your belief, because it is non-verifiable by you. How would you know that I went to heaven? Just because I said so? In fact that is how belief systems work—on the authority of someone else. However, just because the existence of heaven is based on a non-verifiable belief, that does not prove that heaven doesn’t exist. The non-existence of heaven also requires proof in order to be verified. How can you verify that heaven does not exist? To be verifiable, it must be within the scope of our logic and perception, thus being available for research and criticism. Since you cannot prove heaven’s non-existence, much less prove its existence, we can give the benefit of the doubt to the scriptures and accept that there is a heaven.

The Vedas also tell us that heavens exist, but they tell us that heaven is not our goal. Heaven, as well as naraka, a place of pain, is only temporary, because they are within the fold of time. You go there and you come back. According to the Vedas, since heaven is not a final destination, the very effort to get there is meaningless. So although the Vedas provide methods for going to heaven, they also point out its limitations and ask you to consider why you want to go there.

You may say you want to go to heaven because you want to be free from suffering. Yet you won’t be free, because even there you will have a boss—Indra, the ruler of heaven. You may say that as a denizen in heaven, you will have a better standard of living than you now have. But there, too, you will only be an employee. Moreover, another denizen may have a more prestigious job. So in heaven, too, there will be a lot of comparison. The śāstra says that in heaven there are different classes of denizens, enjoying varying degrees of happiness. There is a karma-deva, a deva, an Indra, a BÎhaspati, a Prajāpati, in ascending order of rank and degree of happiness. Therefore, even in heaven there is tāratatamya—comparative degrees of sukha, happiness. Thus, the śāstra does not present heaven as the ultimate end. You may say, “I want to go to heaven because as I am now, I am not okay.” Then I would ask why you don’t become okay. You have so much time available here to work on being okay. “I don’t think I will ever be okay.” So you have made two conclusions: “I am not okay” and “I don’t think I will ever be okay.” What is the basis of your conclusions? “I am over forty years old now.” What does it mean to be over forty? You come to realize that your attempts to make happiness last have not worked. You still feel incomplete. If you are an Indian, perhaps you came to America. Then you got the green card, thinking that once you obtained the green card, everything would work out, but even after getting it, you haven’t changed much. Then you thought that if you got married, you’d be okay—you’d find that elusive everlasting happiness. But even marriage didn’t make you feel totally okay. You thought that if you had a child, you would be okay. After having the child, you find that, well, you’re okay but also not okay. Then you say, “Swamiji, now that I have a child, I don’t want to be here—I want to go to India.” Well, all right, go to India. “I can’t go to India yet, Swamiji. I think I should have some more money before I go.” When will you get that extra money so that you can freely go to India and educate your children there? Year after year, you go on postponing the trip. Your child has become a teenager by now. He comes home at eleven, twelve o’clock at night, and is not available even to talk to. So how will you take him to India? When are you going to talk to that teenager? Naturally, having gone through these experiences, you now have a middle-age crisis. It is not that there were no crises before middle age, but before this time, you always thought you would solve them. By the time you reach middle age, you find that what you have been doing doesn’t work. And your psychological system also doesn’t wait for you to straighten out your life to your liking. All kinds of psychological problems start at this time; unresolved issues from your childhood surface. And thus, not only do you feel that you are not okay, you conclude that there is no possibility of being okay. Then, when somebody promises that in heaven you will be okay, you are eager to believe it. You hold onto that belief for dear life. You hope to go to heaven in order to be happy, and until then, you live like a zombie, because that belief system has given you no hope for this life. It only instructs you about what you need to do so that you will be allowed into heaven. Even after following all the instructions, you will have to wait for judgment day.

The two-fold conclusion that I am not well, and that I can never be well, is a belief that people somehow live with. The śāstra challenges this belief and asks whether you have really inquired into yourself before arriving at this conclusion. You may say, “Yes, I think about myself all the time. Not a day goes by that I don’t think about myself. Every morning when I wake up, I think about the kind of life I live and wonder why I should get up.” This erroneous belief you hold about yourself is avicāra-siddha, established without inquiry. Because it is arrived at without vicāra, inquiry, it is merely a notion. And it is a commonly held notion. What you are immediately aware of—a physical body, mind, and sense complex—seems to be you. You feel limited by it and therefore feel like an insignificant person. Naturally, then, nothing is okay with you.

What Vedānta has to say about you completely negates your notion about yourself. And what it says about you is verifiable. While other traditions may also say that you are limitless, only Vedānta is a teaching tradition, a means of knowledge, which will allow you to clearly see yourself as limitless. The words of the śāstra handled by the teacher point out that what you think about yourself is not true and that you are, in fact, the whole. As you listen to the words, you verify the fact for yourself. Since it is yourself that is talked about, it is verifiable. Vedānta doesn’t talk about heaven; it talks about you, the one who wants to go to heaven. It shows how, in your pursuit of all pleasurable things, you are really seeking only yourself.

Ātmanastu kāmāya sarvaṃ priyaṃ bhavati, “Everything is desirable only for the sake of the self.” These words are attributed to Yājñavalkya, a great sage to whom they say the entire Śukla-yajurveda was revealed. In the BÎhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad, he has a dialogue with his wife, Maitreyi, in which he tells her of his plan to go to the forest and become a sannyāsi so that he can gain mokṣa, liberation or freedom. Renouncing his vast wealth, he explained to her that he would leave half his riches, land and cattle to her. Maitreyi noted that the things he was leaving behind were obviously no longer valuable to him in his pursuit of freedom and asked him whether that same freedom would come to her if she held onto the things he was leaving behind. He said it would not. Why, then, she asked, should she hold onto those things that were of no use in the pursuit of freedom? Instead, she also wanted to pursue that knowledge which leads to liberation.

She asked Yājñavalkya to teach her. It was then that he told her, ātmanastu kāmāya sarvaṃ priyaṃ bhavati, “Everything is desirable only for the sake of the self.” You love an object for your own sake, not for the sake of the object. While you may think that you love objects and people because of what or who they are, in fact, what you love is yourself. Yājñavalkya recited a long list of things that people generally pursue in life. All of them are sought for yourself alone. For instance, you love your spouse for your own sake; you love your son for your own sake. Whatever you seem to love is nothing but the reflection of your own love. When somebody pleases you, you want to be near that person because you want your pleased self. It is the pleased self that you love. If a person displeases you, will you tell that person, “I love you”? Once upon a time, you did tell that person, “I love you,”,and you got married. “I love you,” you murmured. Now you are displeased and you say, “I allow you. Let us have some space.” This is the polite way of saying, “Get lost.” It is something like a person eating a dead pig and calling it pork, to avoid feeling disgusted or guilty. Or he eats a dead cow and calls it steak, so that there is nothing at stake. Even though you can talk of unpleasant things in a nice way, you can’t say, “I love you because you make me unhappy.” The fact that such a statement is impossible means that what I love is not the object which pleases me, but the pleased self.

At times I am pleased; at other times I am displeased. Of the two, which is my true nature? Is the pleased self me, or is the displeased self me? If the displeased self is me, then I should be pleased with being what I am. Thus, I should be happy when I am displeased; I shouldn’t feel ill at ease. But I don’t feel at home when I am displeased. That proves the point that the displeased self is not me. The pleased self is me. In those moments when you are pleased, what obtains is the self. That self is not the wanting self that you usually consider yourself to be. In fact, it is just the opposite. Even though you say, “I am not okay,” you are happy occasionally. At those moments of happiness, what obtains as you is the self that is pleased, which has no lack. You have no complaint to make about that self, and therefore, that self is you. But since, out of ignorance, you take that self for granted, you must come to know the true nature of yourself.

As Yājñavalkya tells Maitreyi, ātmā vāre draṣṭavyaḥ, “The self, my dear, is to be seen,” where ‘seen’ means to be clearly known. You must know the self just as clearly as you see a flower in your hand. How is that to be done? Śrotavyaḥ mantavyaḥ nididhyāsitavyaḥ, “It is to be listened about, analyzed and contemplated upon. ” Śrotavyaḥ—the revealing words of the śāstra, delivered by a teacher who knows their truth, must be listened to; mantavyaḥ—all doubts must be removed so that the truth of the self is cognitively assimilated, and nididhyāsitavyaḥ —it has to be contemplated upon so that you clearly know it is you. Contemplation reveals old patterns of thinking which are obstructions to assimilating the newly discovered truth about the self. One has hypnotized oneself into believing that “I am not okay”, and the world seems to confirm that belief all the time. So I have to dehypnotize myself—first by knowing what I am, and then by living a life which is conducive for this deconditioning. That is the purpose of śravaṇa manana nididhyāsana. Thus, you do not stumble upon the truth—you must hear it from a teacher who knows. And you must verify it for yourself. Since Vedānta is a means of knowledge through which you gain this verifiable truth, what objection can you have to employing this means? If you are a thinker who is able to understand how a means of knowledge works, you will have no problem whatsoever. You just need to employ the means of knowledge to know whether it works or not. For instance, I know very well that in order to see color, I must employ my eyes, not my ears. My eyes are the means of knowing color. Do I need to be convinced of that fact? Do I demand to have other proof that my eyes see? No. I merely need to open them. I am the only authority who can say whether I see or not.

This was made very clear to me when I had an eye examination. I used to get my eyeglasses in India. For 100 or 200 rupees you can go to a doctor and get glasses. If you are a little more adventurous, you can buy your glasses from a sidewalk vendor for fifteen rupees, which is 75 cents. In Bombay and other cities, there are vendors on the sidewalk, selling all sorts of pairs of glasses that you can try on, one by one. So you bring a book to read, in order to test which pair is best. You then come home with a pair of glasses, frame included, for fifteen rupees. But I thought that perhaps I should go to a doctor, pay 100 or 200 rupees, and get a better pair. Then I was advised, “Swamiji, you should get your glasses in the United States rather than in India. Even though you pay more, it is worth it, believe me. You will get the appropriate glasses this way.” So, I went to a doctor’s office while I was in the United States and I was very impressed with the special chairs, lights and equipment. I thought, “This is going to be the real thing—this time for sure I will get the right glasses.” Previously, I was never satisfied that I had chosen the right pair. Now, I thought that the doctor, with his expertise and equipment, would decide what kind of glasses I must have. This time, I thought, my subjectivity would not be involved at all, and I would get glasses objectively chosen for me. The doctor asked me to sit on the chair. Then using a light and other equipment, he examined my eyes. I was impressed. “I think he is going to give me a good pair of glasses,” I thought. Then he placed a piece of equipment like an empty frame on my eyes, and put some lenses in the frames. “Do you see?” he asked. “Yes, I see”. Then he removed those lenses and put another pair of lenses in the frame.

“Now, how do you see?” he asked. “Now I think I see better.”

“Okay.” Then another pair was inserted. “Now, how do you see?”

“Now, I think the previous one was better.” Another lens was inserted. “Okay. Now, how do you see?”

“I think this is better.” Better than what? Already, I am one pair removed from the better lenses. This is a problem. “This one is better”, I said. “Okay. Now, how do you see?”

“Oh, I think this is better.”

“Now?”

“The previous was better.” Yet another lens. “Now?”

“I think the previous one that I had said—that was better.” Already we have two previous ones that were better. And now we don’t know which one was the best because we can’t keep track of all these things. Finally, not wanting to embarrass him any longer or to remain sitting there, I settled for a pair of glasses. And that is how I ended up with a pair of glasses with which I can’t mistake an elephant.

The point is that I am the only one who can say if my eyes see. Since my eyes are the authority, I should use my eyes to know whether they see or not. It is simple. Similarly, I should employ my ears to know whether the ears hear or not. You go to an ear doctor and it is the same routine as with the eye doctor. Previously, a tuning fork was used in ear examinations. The doctor would tune the fork, place it near your ears and ask, “Do you hear? Do you hear?” Now you are given a headphone connected to a machine. Then they press the button: “Do you hear?”

“Yes.”

“Now, do you hear?” Again, it is up to me to know whether I hear or not. Whether my eyes see or not, whether my ears hear or not, it is up to me to know.

A means of knowledge is validated by employing that means of knowledge. That is how we know whether it works or not. If I say that Vedānta, the words of the śāstra, are a means of knowledge, you have to employ them and see whether they work or not. That is because the subject matter is verifiable—the subject matter is you. You have to employ the words and see whether they work or not. Before you do so, you cannot say that they don’t work; you cannot say they are not true. Therefore, a means of knowledge is a proof in itself. It validates itself by doing exactly what it is supposed to do.

Now there may be a question. A student may say, “Swamiji, I listened to Vedānta, but it didn’t work.” That statement can prove that Vedānta didn’t work either because what it says is not true, or because some other condition had to be fulfilled. It may be that my mind is not ready. Or it may be that the one who taught Vedānta is the one who has a problem. I don’t think a teacher who really knows the subject matter can fail to convey exactly what needs to be conveyed. There is a method, a very evolved method of teaching which is highly technical. A context is created and then the nature of the self is taught. Creating the context is essential for the teaching to work. While it is not difficult to understand the teaching, there is a certain technical know-how in employing the method that unfolds who you are. That is because you are what you want to be.

The one you want to know is yourself. It is the very essence of you, the subject, the knower, and it is free from any kind of limitation. There is nothing that is away from you, and yet, you are independent of everything—these two facts have to be totally unfolded. All that is here is you and you are independent of all that is here. If you were not independent of everything, then you could not even move without everything and everyone else moving with you. But since you are independent of everything, and at the same time, everything is you, you can have the understanding that everything is yourself, (sarvātmabhāva), and at the same time, the total freedom that is centered on yourself. You are the whole; you have to discover yourself as such.

For this discovery, we employ a method called superimposition and negation. You have concluded that the mind/body/sense complex is you. We accept that, but then, we negate that part of it, severally, by showing you that while they are not other than you, they are dependent upon you for their existence. You are not limited by them. All of them are limiting adjuncts (upādhi) that you take yourself to be, and are finally negated. They do not limit you because, although what is negated is you, you are more than what is negated. This superimposition and negation is done at every level until you understand, “The whole world is me; I am not the world.” At the level of the physical body, at the level of time, at the level of space, at the level of the universe, at the level of my knowledge, at the level of my memory, at the level of my ignorance—at all levels—I see that this is me, but I am more than all this. That gives me freedom. At every level you discover that all these things are you, and then when they are negated, you discover that you are more than what is negated. You are not dependent upon what is negated. B is A; A is not B. What is negated becomes mithyā—what is dependent upon you. What is discovered becomes satyam, real. This is exemplified in the relationship between an actor and his role. The role depends entirely upon the actor. Although the role may have any number of problems, they are confined to the role; they do not belong to the actor. Thus, an actor can willingly assume the role of a beggar and beg better than a real life beggar. He can study all the beggars in the world and adopt the best form of beggar for his role. He can put them all together and, with all his histrionic talents, and background music to boot, can portray the most authentic beggar. No real life beggar could match his performance. At the same time, however, he doesn’t see himself as a beggar. He knows he is rich, and he also knows he will be richer by playing the role of a beggar for an hour or two. It is a very simple role. He doesn’t require elaborate makeup or costume to play a beggar—his favorite jeans will do. So, when he plays the role of a beggar, he is not really affected by the script. No matter what happens on stage, nothing happens to him. In fact, he enjoys being a beggar for some time. What does that mean? While B is A, A is not B. While the role of the beggar depends upon him for its existence, he is not a beggar. He is more than the role. Through this example, we can understand what it means to know oneself as the reality that gives existence to everything, sarvātmabhāva. While all these things are not other than me, I am not limited by any of them.

That knowledge that I am the reality of everything and at the same time, free from everything, gives me freedom. And Vedānta is the method to gain knowledge. Vedānta is not simply words. It consists of words, no doubt, but they are not descriptive words; they are employed words. You use these words in order to remove them. You use them, remove them, and make them stick at the point where they have to stick. The capacity to make you see is not in the written words alone. In fact, the whole Vedic tradition is an oral tradition, because in order for the teaching to work, it cannot simply be read. While the books can be of use to support the teaching, one has to expose oneself to the words as employed by the teacher. Therefore the śruti says,

parīkṣya – examining; lokān – the worlds/experiences; karmacitān – gathered by karma; brāhmaṇaḥ – a Brahmin [a thinking person]; āyāt – would gain; – nirvedam dispassion; nāsti – there is no; akÎtaḥ – uncreated; kÎtena – by action; tad-vijñānārthaṃ – in order to know that; saḥ – he; according to propriety (with sacrificial twigs in hand); abhiyagacchet would approach; gurum eva – only/indeed a teacher; śrotriyaṃ – who knows the śāstra; brahmaniṣṭham – and whose commitment is in Brahman.

Examining the worlds/experiences gathered by karma, a Brahmin [a thinking person] would gain dispassion [understanding that] the uncreated is not [accomplished] by action. In order to know that [uncreated] he, would approach in the proper way only/indeed a teacher who knows the śāstra and whose commitment is in Brahman.

The śāstra tells us to go to a teacher who can employ these words properly, who doesn’t simply bandy these words about. Some teachers do simply throw words around. For instance, if you come to me and ask, “Swamiji, what is ātma?” and I say, “Ātma is eternal, immortal, supreme, infinite bliss,” I will not have taught anything, and you will not have learned anything.

Many teachers do make these statements, sometimes stringing all the words together, or sometimes just using them one by one. “You are eternal.”

“What is eternal, Swamiji?”

“Eternal is immortal.”

“What is immortal, Swamiji?”

“Eternal. It is infinite.”

“Why should I know the infinite, Swamiji?

“Because it is bliss.”

“Oh, how can I get that bliss, Swamiji?”

“You should experience it.”

“How will I experience it, Swamiji?”

“When your mind doesn’t think.” Well, obviously, this is all nonsense. “Eternal, immortal, infinite consciousness” has no meaning. It is exactly like a tape recorder playing a meaningful message, but at high speed, so it is undecipherable. It is the same thing here. The teacher who bandies words like this doesn’t know what he is talking about. Thus, it is said, the teaching must come from a person who knows what it is all about.

The Gītā also has a message for us on this topic. In all of its seventeen chapters, the first chapter is the only one that doesn’t require a guru to teach it. The first chapter, which contains Arjuna’s story, can be replaced by your own. You can write your own first chapter, your own autobiography, telling where you were born and all the important events of your life. And then it is you who tell Krsna: śiṣyas te’ham śādhi mām tvām prapannam, “I am your śiṣya, your student. Please teach me, who has surrendered to you.” “Overcome by faint-heartedness, confused about my duty, I ask you,” kārpaṇya-doṣopahata-svabhāvaḥ pÎcchāmi tvām dharma-sammÍḍa-cetāḥ (BG 2.7). Please teach me whatever is right for me. I clearly see that I cannot get rid of this sorrow by the means that I have been following so far. Please help me out, I am your student, śiṣyas te’ham. Thus, the first chapter of the Gītā is your chapter. Arjuna can be replaced by any given person. You don’t require a guru for that; you require only yourself.

The teaching of the Gita starts with the second chapter. You are grieving for that which is not deserving of grief, and yet, you speak words of wisdom, aśocyān anvaśocas tvam prajñā-vādāṃś ca bhāṣase (BG 2.11). This is the teacher’s opening statement: You are sad for no legitimate cause. “You say I am sad for no real reason? But I do have real reasons to be sad. I lost my job and I don’t think I can find another one. I have to make mortgage payments. Surely, these are legitimate reasons to be sad. How can you say I don’t have reasons?” You may have situations to think about and challenges to face, but you have no reason to be sad. “Oh. Do you require more reasons for being sad?” There is no reason big enough to make you sad. “What?” There is no reason that can make you sad. “That is utopia. Everybody’s sad. I know that you, too, are sad.” How did you come to that conclusion? “Because you are a human being.” You have jumped to the conclusion that if you are human being, you should be sad. You have jumped to that conclusion, and it is a suicidal conclusion. It is something like a parachutist jumping from a plane and his parachute failing to open—he jumps to a conclusion. Don’t jump to such conclusions about yourself.

To understand the opening statement of the Gītā, you must know all of the seventeen chapters. To understand one verse, you must know the vision of all the verses together. Yet, unless you know each verse, one by one, you will not know the vision of all the verses. Unless you read each verse, you can’t get the total vision. Unless you have the total vision, you can’t get to know the meaning of a single verse. You are caught in a catch-22 situation. It is like a man waits to be psychologically healthy before he will marry, yet unless he marries, he will not become psychologically healthy. We have a similar catch-22 problem here. In this situation, you need a teacher who knows the whole. Knowing the whole, he can make you see the single verse as well as the whole. That is why he is called ‘guru’. The etymological meaning of the word guru is: The syllable gu stands for darkness and the syllable ru stands for the one who removes it, gukāro andhakāraś ca rukāras tannivartakaḥ. The one who is the remover of andhakāra, darkness, is called a ‘guru’.

Then we may ask how the guru got this knowledge. Did he figure it out by himself, verse by verse? If so, then the student can, too. That is not so. The guru received the knowledge of the śāstra from his guru. Or from her guru. In India, there were a lot of women teachers. Since this knowledge of the self has nothing to do with being male or female, the gender of teachers is not traced. Then you may ask another question: “Who was the first guru?” I would tell you that the first guru was the disciple of his guru. If you still persist, I would then ask you a question: “Who was the first father?” Remember that ‘father’ also includes mother. After all, both parents were necessary. You can keep tracing your ancestry until you can trace it no longer. Finally, you have to say that the first father was someone who was not caused. The uncaused cause is the first father. Janakaḥ sarvasya jagataḥ janakaḥ iti, the father of the whole world is “father”.

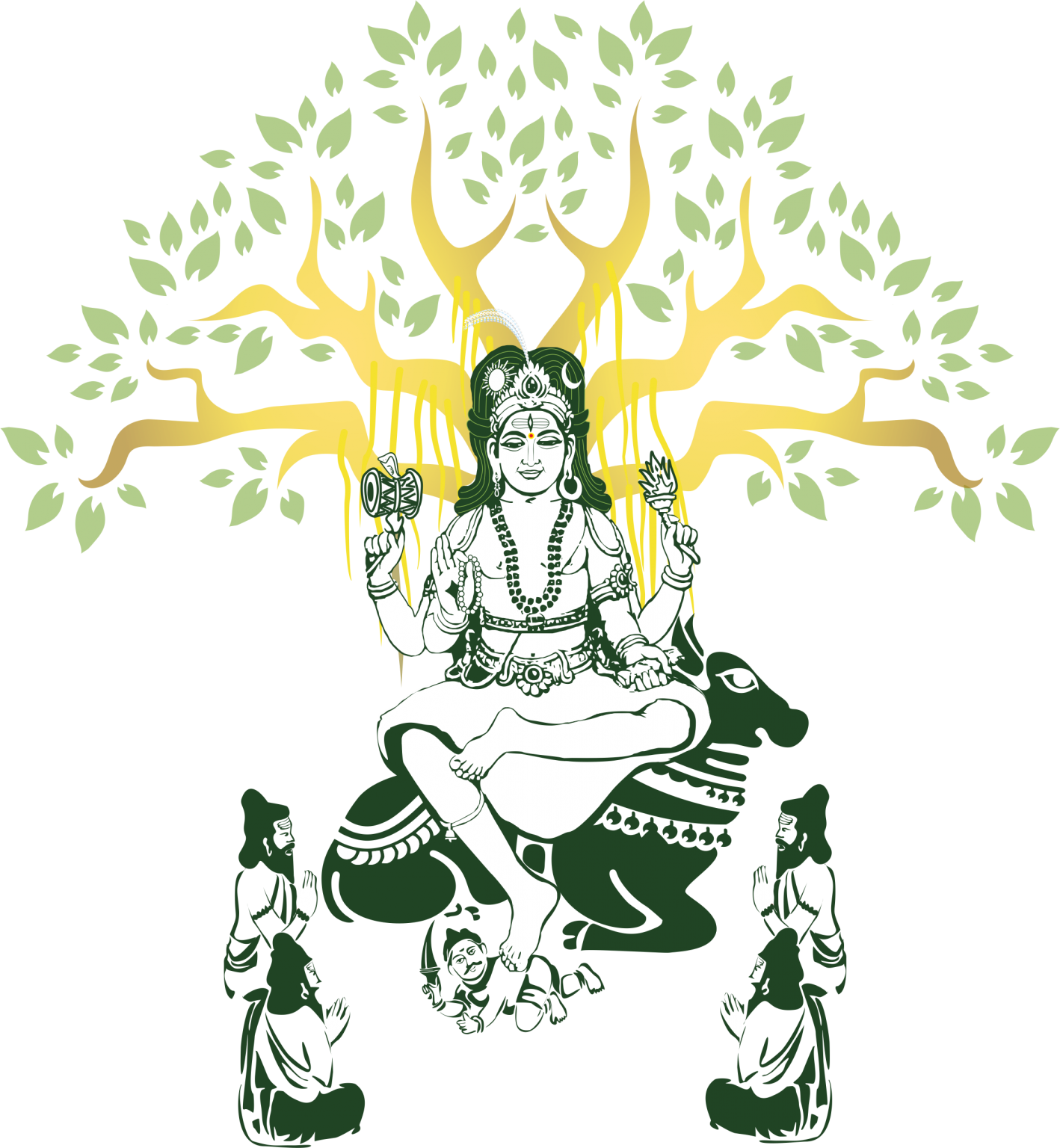

If the Lord is the first father, the uncaused cause, who is in the form of this creation, and who is, therefore, the source of all knowledge, we have a name for that Lord: DakṣiṇāmÍrtiḥ. Being the cause, he is all knowledge, especially spiritual knowledge. You will find the Lord is presented in this form as aṣṭamÍrti, the one who has eight aspects. The first five aspects are the five elements. In the Veda the world, presented in the form of five elements—ākāśaḥ, space, which includes time; vāyuḥ, air; agniḥ, fire; āpaḥ, water; and pÎthivī, earth. In this Vedic model of the universe, the five elements are non-separate from the Lord. In fact, these five elements constitute the Lord’s form, which is this universe. The next two aspects are represented by the sun and the moon. When, as an individual, I look at this world, what stands out in the sky are the sun and moon. The moon represents all planets other than earth, and the sun represents all luminous bodies. The eighth aspect is me, the jīva—the one who is looking at the world. These eight aspects are to be understood as one whole. This is the Lord. When we look at the form of DakṣiṇāmÍrti, we can see representations of the five elements. Space, ākāśa, is represented by a ḍamaru, a drum, in his right hand. In order to show space in a sculpture, it needs to be enclosed. Empty space is enclosed in the ḍamaru, enabling it to issue sound, or śabda. Next, vāyu, air, is represented by DakṣiṇāmÍrti’s hair with the bandana, the band, holding his hair in place against the wind. Bandana is a Sanskrit word which comes from the root band, to bind. In his left hand, you will see a torch, which represents agni, fire. Āpa, water, is shown by the Gaṅga, in the form of a Goddess, which you can see on DakṣiṇāmÍrti’s head. PÎthivi, the earth, is represented by the whole idol. Then there are people, the jīvas, Sanaka, Sanandana, Sanātana and Sanatsujāta, who are the disciples of DakṣiṇāmÍrti, sitting at the base of sculpture. The sun and moon are also shown in this form of the Lord. On the left side of DakṣiṇāmÍrti you will find a crescent moon, and on his right side there is a circle, representing the sun—a whole circle. So we see five elements, two planets and the jīva constituting the aṣṭa-mÍrti-bhÎt, the Lord of these eight factors that are the whole.

You can worship DakṣiṇāmÍrti as the Lord, the one who is aṣṭamÍrtibhÎt, or you can invoke him as a teacher, because he also is in the form of a teacher. His very sitting posture, āsana, is the teacher’s āsana. What does he teach? Look at his hand gesture. That shows what he teaches. His index finger, the one we use to point at others, represents the ahaṅkāra, the ego. The other three fingers represent your body, deha, mind, antaḥkaraṇa and sense organs, prāṇa. They also may be seen as the three bodies, śarīras, the gross, subtle, and causal. This is what the jīva mistakes himself to be. The aṅguṣṭha, the thumb, represents the Lord, the puruṣa. It is away from the rest of the fingers of the hand, yet at the same time, the fingers have no strength without it. In this gesture, mÍdra, in DakṣiṇāmÍrti’s right hand, the thumb joins the other fingers to form a circle, teaching that the jīva, who takes himself to be the body, mind and senses, is the whole. The circular hand gesture visually states the entire upadeśa, teaching: tat tvam asi, “You are That.” Just as a circle has no beginning or end, you are the whole. That is the final word about you. Nobody can improve upon that vision; no culture can improve upon it. Even in heaven, it cannot be improved upon, for the whole includes heaven. Therefore, you have the final word here, because you are everything. It is better that you know it. That teaching is contained in the Veda, represented by the palm leaves in the left hand of DakṣiṇāmÍrti. And to understand this, you require a mind that has assimilated certain values and attitudes and has developed a capacity to think in a proper and sustained way. This can be acquired by various spiritual disciplines represented here by a japa-māla. The fact that the Lord himself is a teacher, a guru, means that any teacher is looked upon as a source of knowledge. And the teacher himself should look upon Īśvara, the Lord, as the source of knowledge. Since the Lord himself is a teacher, the first guru, there is a tradition of teaching, so there is no individual ego involved in teaching.

DakṣiṇāmÍrti is seated upon a bull, which stands for tamas, the quality of māyā that accounts for ignorance. This is the entire creative power of the world and DakṣiṇāmÍrti controls this māyā; Then, there are bound to be obstacles in your pursuit of this knowledge. DakṣiṇāmÍrti controls all possible obstacles. Underneath his foot, under his control, is a fellow called apasmara—the one who throws obstacles in your life. This tells us that although there will be obstacles, with the grace of the Lord, you can keep them under check and not allow them to overpower you. There is no obstacle-free life, but obstacles need not really throw you off course; you keep them under control.

Thus, the whole form of DakṣiṇāmÍrti invokes the Lord who is the source of all knowledge, the source of everything, the one who is the whole, and who teaches you that you are the whole. He is DakṣiṇāmÍrti, the one who is in the form of a teacher, guru-mÍrti. We invoke his blessing so that all of you discover that source in yourself. If this self-discovery is your pursuit, your whole life becomes worthwhile. This project of self-discovery should be the projectmof everyone. That is the Vedic vision of human destiny.