Swami Dayananda Saraswati

Excerpt from the forthcoming Tattvabodha, Arsha Vidya Research and Publications, 2009

What is samādhāna?

Cittaikāgratā

Right in front of you, agre, there is only one thing, eka. This is ekāgra, and ekāgratā is the abstract noun. The meaning of samādhāna is the status of your mind, citta, focusing on one thing at a time, citta-ekāgratā samādhānaà. This is an accomplishment for oneself. Citta-ekāgratā has to be mentioned, because people may have difficulty in keeping the mind in one track of thinking. To keep the mind in a particular track of thinking for a length of time is an accomplishment, because the mind moves. Citta-ekāgratā is the capacity to bring it back. The mind’s nature is to move; in fact, it has got to, because only then can you know things. But then, it can not only move, but move away from your chosen occupation. And therefore, you should have the capacity to bring it back. This is called samādhāna.

You all have this citta-ekāgratā, capacity to keep the mind in a given track. People often tell me, “Swamiji, I have no concentration.” This is a common thing. If somebody confirms that, it is another form of manipulation. If you want to manipulate people, tell them they should develop concentration. “Yes, Swamiji, how can I develop concentration?” Everybody will ask you that. Even if you ask God to develop concentration he will ask how, because this is a common problem.

In fact, there is no problem at all. We will make a problem out of no problem. Who has no concentration, tell me? You may say, “I have no concentration because when I read the book, my mind goes all over the place.” Which book? “My textbook, Sanskrit.” You said it. Suppose you are reading about a particular topic that you like, or the book is a novel by an author you love. There, you find concentration. You will read the whole book in one day. From where do you get this concentration? You can understand that unless you have it, you can’t apply that concentration under any circumstances. So, in what you are interested in, there is concentration. But what you are interested in, what you have a value for cognitively, intellectually, you may find is not compelling, emotionally. There is no hero, no drama. Sanskrit is rāmaḥ, rāmau, rāmāḥ. How did rāmaḥ become rāmāḥ? It is a problem. There are sūtras for that, so you not only have to know rāmāḥ, you also have to know how it became rāmāḥ. There are two problems. But once you begin loving that, you have concentration, because there is a certain emotional satisfaction in it. That must be there. Everybody has concentration, unless there is some pathological problem, so for somebody to say that you must have concentration is another form of manipulation. As though the person saying it has concentration. Everybody has concentration; it is a question of discovering that particular attraction for a topic. You have to discover that. Any topic, once you get involved in it, once you begin to understand it properly, elicits concentration. So no one can say that he or she has no concentration.

Still, someone can say, “Swamiji, if I have concentration, why, when I am chanting a mantra, does my mind move away? It goes all over.” It is the mind’s nature to go all over. It should not be stagnant. Otherwise you won’t be able to know anything. The thought frame must be momentary, because you can’t see the motion unless it is. It has to be momentary, like a movie. Your mind is not like a Polaroid camera. It is momentary, so you don’t see a single picture. It goes on taking pictures; that is how the mind works. It has to move; the Bhagavadgita confirms it: caṅcalam hi manaḥ. “The mind has to move, okay, but why should it not chant, when I want it to? When I am repeating something mentally, my mind moves away from what I am repeating.” Do you know what? This is called meditation. Part of the definition of meditation is to bring back the mind to what you are doing. That is what meditation is, so you cannot complain to me anymore that you cannot meditate.

Bringing the mind back to the object on which you are dwelling is the definition of meditation. So nobody can really complain, “My mind moves away.” Bring it back. Bringing it back is meditation. You can no longer say that the mind moves away, because you understand the logic. Moving away is natural, but if you don’t bring it back, there is no meditation.

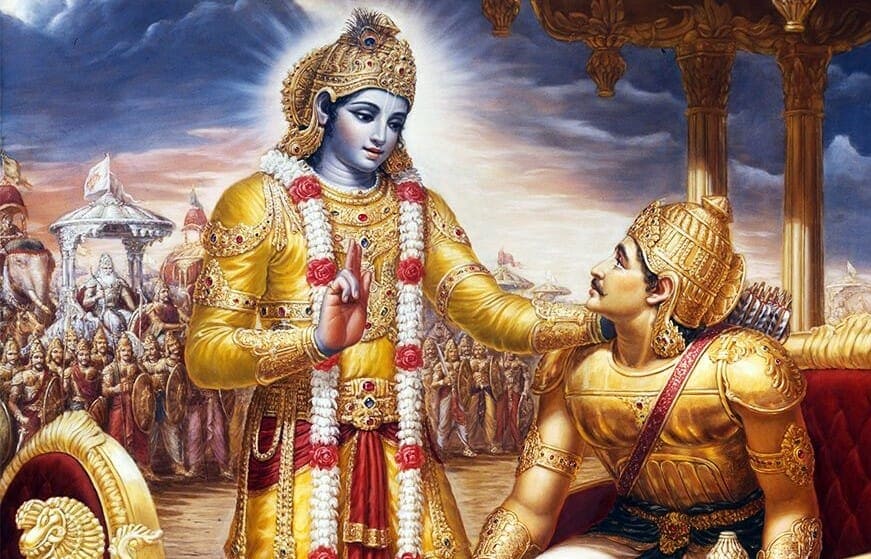

Your attempt to bring it back is meditation. “Whenever it moves away you bring it back” is the advice given by Bhagavān, in the Bhagavadgétā, yato yato niścarati tatastato niyamyaitad (6.26). That is meditation. And that capacity to bring it back is what is called citta-ekāgratā samādhānaà.

Samādhāna can also be taken as a mind that is not interested in too many things, or in doing many things at the same time. Trying to do many things at the same time is so common that we even have a new word for it—‘multitasking.’ This is a particular kind of habit that is not helpful in this pursuit, so we need to have samādhāna. And also, too many irons in the fire is a problem. When there are too many things out there to do, we need viveka and vairāgya, as already mentioned. Here, a certain citta-samādhāna is also required. You have only one thing in front of you, and this is what you are seeking now. That is the main, the predominant occupation. “This is what I want now, this is what I am doing now, at this time in

my life.” So what you are doing draws your attention, has you, for the time being. Now Vedanta has you—and Sanskrit also. Nothing else has you, because you are committed to them. This is samādhāna.