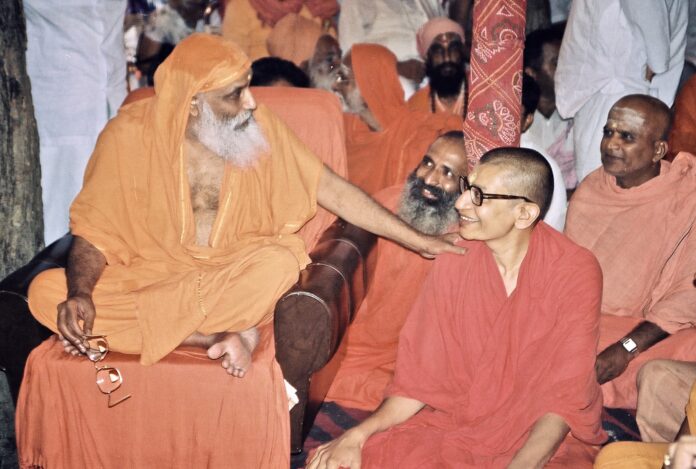

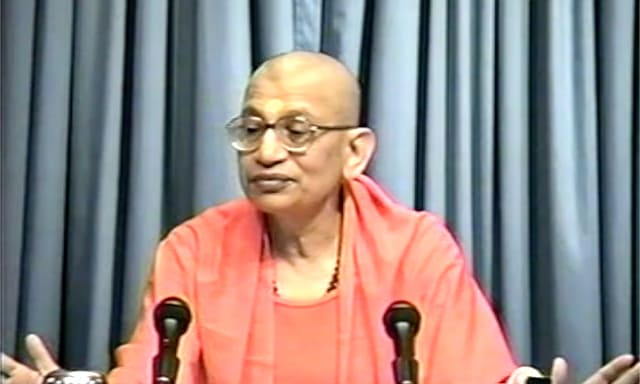

Satsang with Sri Swami Viditatmananda Saraswati

tad viddhi praṇipātena paripraśhnena sevayā |

upadekṣhyanti te jñānaṁ jñāninas tattva-darśhinaḥ || 4-34 ||

praṇipātena – by prostrating; paripraśnena – by asking proper questions; sevayā – by service; tat – that; viddhi – understand; jṣāninaḥ – the wise; tattva-darśinaḥ – those who have the vision of the truth; te – for you; jṣānaṁ – knowledge; upadekḥyanti – will teach

Understand that (which is to be known) by prostrating, by asking proper questions (and) by service. Those who are wise, who have the vision of the truth, will teach you (this) knowledge [Bhagavadgītā 4- 34].

Deliberate upon the Self with the help of a teacher

Tatviddhi, may you know that. May you know the means of gaining that knowledge, and may you know the process through which you may gain the knowledge. Knowledge is gained as a result of teaching. It is a result of vicāra, an enquiry or deliberation upon the nature of the Self. Whenever we want to know anything, we should enquire into its nature. We should deliberate upon what it is. That process of enquiring or deliberation is called vicāra. We want to know the Self, and therefore, have to deliberate upon or enquire into the nature of the Self.

How do we perform that enquiry? How do we deliberate upon the nature of the Self? We have to deliberate upon the meaning of the statements of the upaniṣad. The subject matter of the upaniṣad is the Self, and therefore, the statements of the Upaniṣads reveal the true nature of the Self. Therefore, an enquiry into the nature of the Self amounts to understanding the meaning of the statements of the Upaniṣads. To understand what the Upaniṣads reveal, we should understand the real meaning of the statements of the upaniṣad, and determine the purport of the statements of the Upaniṣads. We need the help of a teacher to understand the statements of the Upaniṣads.

Vedānta says one simple thing, tat tvam asi, ‘that thou art’. What does it mean? What is the meaning of the word tat, or that? What is the meaning of tvam, or you? What is the meaning of the oneness or equivalence of these two words? This is what Vedānta is about. Vedānta is all about tat tvam asi, the subject matter of all the Upaniṣads. Therefore, Lord Krishna tells Arjuna, may you approach a teacher.

We all seek the limitless

Muṇḍakopaniḥad says:

परीक्ष्य लोकान्कर्मचितान्ब्राह्मणो निर्वेदमायान्नास्त्यकृतः कृतेन ।

तद्विज्ञानार्थं स गुरुमेवाभिगच्छेत्समित्पाणिः श्रोत्रियं ब्रह्मनिष्ठम् ॥ १२ ॥

parīkṣya lokānkarmacitānbrāhmaṇo nirvedamāyānnāstyakṛtaḥ kṛtena |

tadvijñānārthaṃ sa gurumevābhigacchetsamitpāṇiḥ śrotriyaṃ brahmaniṣṭham || Muṇḍakopaniḥad 1-2-12 ||

Having analyzed the worldly experiences and achievements acquired through karma, a mature person gains dispassion and discerns that the uncreated (limitlessness) cannot be produced by action. To know That (limitlessness), he should go, with twigs in his hand (servitude), to a teacher who is learned in the scriptures and who is steadfast in the knowledge of himself [Muṇḍakopaniḥad 1-2-12].

A thinking person, a deliberate or contemplative person, enquires into his own life and takes stock of his life. He deliberates upon his goals, accomplishments, upon what he is doing, and what he wants in his life. It is very important to determine what we want in our life. It is important to know that what we want in life is what every human being wants: unconditional freedom, happiness, and peace. I need to understand that what I am seeking is limitless, what I am seeking is wholeness or completeness, and that I cannot be satisfied with anything that is limited. When this is clear, the question is how is it to be achieved?

The limitless is to be known

Parīkṣya lokān karmacitān or, karmacitān lokān parīkḥya, analyzing or deliberating upon accomplishments or achievements possible through the performance of various actions. In doing so, one determines that every achievement is limited, nāsti akśtaḥ kśtena. Kśtena, by doing actions, you can achieve things but each one of them is going to be limited. Any effort is limited, and therefore, anything that is achieved as a result of a limited effort is also going to be limited. Thus, no amount of achievements or accomplishments are ever going to create in me a sense of completeness. Then how do we achieve that? We can achieve that when we understand that completeness is not something to be achieved. Akśtaḥ, it is uncreated. If it is not limited in time or place, then it must be here and now, and therefore not created. Anything that is created is going to be perishable. In order that this freedom or happiness is not perishable, it should also not be created. What is not created must be here and now! What is now, is not something to be achieved, but something to be known.

This understanding is the result of viveka or discrimination. Pujya Swami Dayanandaji would call it emotional maturity. The mind becomes contemplative and sees the basic reality of life: I am seeking to be free from all limitations; I am seeking to be limitless. One realizes that this limitlessness is not something to be achieved, but something to be known.

The desire still remains, but the nature of desire has now changed. So far, it was a desire to become something, a desire to achieve something, and a desire to accomplish something. Now it is transformed into a desire to know the Self. The means that we employ to fulfill a desire always depends upon the nature of the desire. If the desire now is for knowledge, then we should adopt an appropriate means to fulfill that desire. Therefore, Lord Krishna says, may you approach a wise and learned teacher.

The need for a guru

Knowledge can be gained as a result of upadeśa, instructions or the teacher’s unfolding of the words of Vedānta. They always seem to make a point that this knowledge should be gained from the teacher. For example, explaining this verse from the Muṇḍakopaniḥad, Śrī Śaṅkarācārya says, “śāstrajṣopi svātantryena brahma-jṣānānveḥaṇam na kuryāt”, even if one is very learned, one should not independently pursue the enquiry into the nature of the Self. That is, one should always gain this knowledge from the teacher. This sounds very convenient for the gurus or teachers; everybody is required to go to a guru!

What I want to know is my own Self. It is a very peculiar subject. I already know myself, but I know it wrongly. I entertain a number of false notions about myself, but do not know that the notions are wrong. I am quite convinced about the conclusions and opinions that I have about myself: I am a human being; I am subject to birth and death; I am limited; I am a seeker; I am needy. The ego entertains all these false notions about itself.

Therefore, what we now need to do is to inquire into the nature of the ego. Are these notions true or are they false? Is this the true nature of myself? In order to determine the reality of something, we should become objective. We should be able to create an emotional distance, like a scientist who is objective with reference to the object that he is investigating. He has no preconceived notions or agenda about his object of inquiry. He is very objective and has an open mind to accept whatever the investigation reveals.

The investigation into the nature of the Self would also require me to be objective with reference to my own self, objective with reference to my own present notions and conclusions. Objectivity means detachment. That means I do not have any agenda with reference to what I should be. I should have an open mind. It is very difficult for the ego to inquire into its own nature. Therefore, it becomes necessary for me to stand on another platform from where I can look at the ego, enquire into the ego. That is the platform of the scriptures. The Upaniṣads are, in fact, an investigation into the nature of Self. Therefore, I must identify with the Upaniṣads and look at my own self from the perspective of the Upaniṣads. Then alone can I recognize what is false as false. Then alone can I see that the various notions that I entertain are not correct, and then let them go. That is called an open mind, a learning mind, which is willing to let go of anything that is discovered to be false.

I cannot go to the Upaniṣads directly, however, because I will interpret the Upaniṣads in my own way. Therefore, we seek the help of a teacher. The teacher is one who has studied the Upaniṣads from his own teacher, and gained the vision of the Upaniṣads. Therefore, he is as good as the Upaniṣads. That is the importance of the teacher.

Importance of identifying with the guru

It is not the person with whom you want to identify, but the vision of the person. It is what the person knows and what the person stands for that you want to identify with. Identification with the teacher will make me objective with reference to my own notions and my own conclusions. How can I identify with the teacher? What is required is śraddhā or trust, and bhakti or devotion. This will enable me to identify with the teacher and de-identify with the ego. It is very important to de-identify with the ego and for this, identification with the teacher becomes important. The devotion that the student has for the teacher, and the trust that the student has for the teacher will enable him to become detached from his own ego, his own conclusions, and his own opinions. It will let him deliberate upon them and investigate their reality from the standpoint of the teacher or the Upaniṣads.

We must understand what the roles of the guru and the śiḥya are, as far as Vedānta is concerned. Elsewhere, the relationship between the teacher and the student may be different, but as far as the study of Vedānta is concerned, the relationship between the teacher and the student is a very practical one. The teacher sees something, and I also want to see that. In the Kaṣhopaniḥad, Naciketas asks Lord Yamaraja for the truth, which is beyond dharma and adharma, beyond the past, present and future, and beyond all cause and effect.

anyatra dharmād anyatrādharmād anyatrāsmāt kśtākśtāt

anyatra bhūtācca bhavyācca yat tat paśyasi tad vada

Please tell me of that which you see as different from dharma and adharma, different from this cause and effect, and different from the past and the future. [Kaṣhopaniḥad, 1-2-14]

The teacher unfolds the upaniṣad with reference to his own vision. The student wants to see what the teacher sees, hence, the identification with the teacher. Therefore, in the first line of this verse from the Bhagavadgãtà, Lord Krishna teaches us how to develop identification with the teacher.

Developing śraddhā

Developing sraddha is a process that begins when you are exposed to the teacher. Sraddhā may not develop right away. It is not that you identify with the teacher in one day, though you may be able to do so if you are lucky. Suppose the teacher touches your heart, and is able to appeal to you, then that is the starting point; and from that you have to build up that śraddhā and bhakti in your heart. The identification with the teacher is complete when both śraddhā and bhakti have been discovered. That is when the student is attuned to the teacher. It is like tuning our transistor to the broadcasting station, which enables us to receive music. A teacher is like a broadcasting station, which simply broadcasts what is. He receives from the scriptures and broadcasts to the students. It is up to the student to ready the mind to receive his teaching. This process of tuning up is called developing śraddhā and bhakti. This is how Vedānta talks about śraddhā.

Śraddhā is generally translated as faith or trust, but the term should be understood as being an implicit trust or faith coupled with devotion and reverence. It is not merely trust. We have trust in our physicians too. We all require trust in our life; without trust, we cannot live our life. When somebody serves me food, I must have enough śraddhā or trust that it is alright for me to eat it. Even when someone tells us something, we have to have śraddhā that what they are telling is what they mean. Life would be very difficult without śraddhā. Very often, our trust is violated, but if I cannot trust anybody, it leads to my own destruction. Therefore, śraddhā is required because if I am suspicious of everything, I cannot live. There has to be trust everywhere.

The Vivekachudamani defines sraddhā as follows:

śāstrasya guruvākyasya satyabuddhyāvadhāraṇā

sā śraddhā kathithā sadbhiḥ yayā vastūpalabyathe

Ascertainment of the scriptures and of the words of the guru with conviction about their truth is called śraddhā by the good and as that by which knowledge of Reality is obtained [Vivekacūḍāmaṇi, 26].

Śāstrasya guruvākyasya satyabuddhyāvadhāraṇā, a kind of conviction that arises in my mind that what the teacher says and what the scriptures say is right. This conviction has to happen by itself; I cannot do this śraddhā. A response arises in my heart when I listen to the words of the teacher, “This is right. This is right.” If my heart responds this way when listening to the Upaniṣads, then I am enjoying śraddhā. When that happens, we are favorably disposed to receive the teaching. Sraddhā opens a channel by which the knowledge from the teacher can flow to the heart of the student because the mind does not resist it.

Śraddhā implies an open and trusting mind

If my mind is resisting what I am told or questioning what I am told, it is not a learning mind. A questioning mind is not a learning mind. Asking a question is one thing and questioning somebody is a different thing. Asking a question is always encouraged in Vedānta. In fact, unless you ask a question, a Vedāntic teacher is not supposed to tell you anything:

नापृष्टः कस्य चिद् ब्रूयान्न चान्यायेन पृच्छतः ।

जानन्नपि हि मेधावी जडवल्लोक आचरेत् ॥ ११० ॥

nāpṛṣṭaḥ kasya cid brūyānna cānyāyena pṛcchataḥ |

jānannapi hi medhāvī jaḍavalloka ācaret || Manusmṛti, 2-110 ||

Unless one be asked, one must not explain (anything) to anybody; nor (must one answer) a person who asks him improperly; let a wise man though he knows (the answer), behave among men as if he were an idiot [Manusmṛti, 2-110].

One should not communicate unless a question is asked. Just because somebody asks, you are not obliged to answer if you feel that the question is not fair. Sometimes people ask you a question not because they want to know, but because they want to test you. There can be different intentions in asking questions also. A question may even be asked in an improper manner. There is a way of doing things. We need not equate it to formality, but there is a way of doing things.

When we ask a question of a teacher, there must be a reverence, and a desire to know. It should reveal the jijṣāsa or the desire to know in my heart. It should also reveal a certain trust that I have in the one of whom I am asking the question. Then alone is it called a question that is properly asked. Otherwise, says the Manusmṛti, even if somebody asks a question, you need not reply. Indeed, you should not reply to it. You must pose as though you do not know, jānannapi hi medhāvī jaḍavalloka ācaret. Be jaḍavat, like one who does not know. The asking of questions is always encouraged as long as it is a genuine question. However, as we discussed before, this knowledge should not be imparted unless a question is asked.

Sraddhā means maintaining an open mind. As far as Vedānta is concerned, what the teacher tells us can be verified. It may take a little while for us to verify it, we may have to wait until we gain a certain maturity of mind to verify the truth of what the teacher says, but we can verify it nevertheless. As Pujya Swami Dayanandaji would say, śraddhā is faith or trust pending discovery. Until you discover the truth of the teaching for yourself, it is a matter of faith. It is not blind faith; it is faith, which is born of conviction. The conviction in my heart that what the teacher says is right is called śraddhā. That frame of mind or disposition of mind is called śraddhā. Yayā vastūpalabyathe. It is a very important element in learning. Lord Krishna himself will subsequently say that in the fourth chapter. (Bhagavadgita, 4-39). Here, in the first line of this verse, Lord Krishna tells us how to establish this kind of proper relationship.

Establishing a proper relationship with the teacher

This is a very interesting verse. A proper relationship with the teacher encourages the teacher to impart the knowledge to you. When the right relationship is established, the knowledge will definitely take place. How can we make this happen? Lord Krishna says, “Tatviddhi praṇipātena paripraśnena sevayā”, by praṇipāta or prostration, paripraśna or through questions, and through seva or service. We have to change the order somewhat, to praṇipātena sevayā paripraśnena, to mean by prostration, through service and lastly, through questioning.

Praṇipāta

Praṇipāta is prostration at the feet of the teacher. It is a salutation or dhīrga namaskāra, a long prostration. It is the aḥṣānga-namaskāra, with all eight limbs touching the ground. The eight limbs include the mind as well as speech, in addition to the forehead, shoulders, chest, hands, knees, and feet. I express my devotion through words, and with the right attitude of mind. This is the traditional aḥṣānga-namaskāra. It is in south India that you see people doing this namaskāra. It is not a common practice in north India. When the body is on the ground like a danda, a stick or a staff, it is called dandavat namaskāra. That is the praṇipāta talked of here.

Praṇipāta helps cultivate devotion

Dhīrga namaskāra is a form of paying obeisance. Every form has a spirit behind it. The form is not as important as the spirit behind it, but serves to represent or reveal the spirit. “Swamiji, what is the big deal about how I prostrate? When I know I have devotion for my teacher, how does it matter?” Well, if you have the devotion, then why don’t you prostrate? When the spirit is there, there is no difficulty in having the form.

“But Swamiji I do not believe in doing things if there is no spirit inside”. Then also, I suggest you prostrate to the teacher. Prostrate, even if you don’t have that devotion. The form will create the spirit. Ideally, the spirit should inspire the form, but if the spirit is not there, the form will be able to invoke the spirit. That is why we ask the children to prostrate in temples and at the feet of the elders. This is so that they adopt the form. As a child, he or she does not know. For a child there is no form. He does not understand why he should do so. Perhaps, the child does not want to prostrate, but we still make them. That is the idea of form. Although the form is secondary to the spirit, we should not undermine the importance of the form.

The form is a ritual. A ritual implies the form and various forms are given to us in order to express our emotions, our attitude, and spirit. Life is always full of rituals meaning that there is always a way of doing things. There is always a form for doing everything. For instance, clothes should be worn in a proper way. When you go out for dinner you dress in a certain way, when you go to work you dress in a different way, when you go to temple, you dress in another way, and when you are at home you dress in yet another way. You could put on any clothes anywhere, but you still do it in a specific way, and that is the way to do it. Thus, there is the way of doing everything. That is called ritual, a traditional form, which is prescribed and adopted.

The spirit and the form go together. The advantage of a form is that even if the spirit is not there, we can bring in the spirit. As Pujya Swami Dayanandaji would say, you should ‘physicalize’ your worship. Suppose you don’t have devotion, but wish that there should be devotion in your heart, you have a value for it. At that time, do what you would do if you had devotion. It is called, ‘fake it till you make it’. In other words, if you don’t have it, pretend as though you have devotion and do the ritual as though you have it. In course of time, the devotion will come. Thus, the spirit brings about the form, but in turn, the form can also invoke the spirit. This is praṇipāta.

Praṇipāta indicates surrender

Tatviddhi praṇipātena, may you offer a long prostration to the teacher. Touching the feet of the teacher with my head shows my humility, my spirit of surrender, and my spirit of offering myself as if saying, “I am at your disposal. I have full trust in you. I know that you will be able to teach me or give me what I need”. It is the trust or the śraddhā that is, in fact, indicated when this prostration is done. By prostrating, I also declare that I am only as good as your feet. Ultimately, I have to reach your head, or achieve your way of thinking, but at present, I am beginning at your feet.

This is one formality, one form. Seva helps in becoming attuned to the teacher After offering myself to the teacher, I commence seva, service to the teacher. As you know, in the Vedic times, the student would live with the teacher during the period of study. That is why the place was called a gurukulam meaning the home or kulam of the teacher, guru. The student lived in the teacher’s home and became part of his family. He was looked upon as a son or daughter by the teacher and his wife. Thus, before the upadeśa or teaching actually takes place, it is necessary to do whatever is required to develop a familiarity with the teacher.

Seva or service to the teacher is at a personal level, which is taking care of all his needs. Typically, the disciple would attend to all the needs of the teacher. He would be awake before the teacher woke up, warm the water for his bath, and make all other preparations as required. If the teacher performed homa every morning, he would prepare for that. He would beg bhiksha or food for the teacher, offer it to the teacher, and then partake of whatever remained. In the evening, he massaged the feet of the teacher if required. He waited until the teacher slept before he went to bed. Thus, the student awoke before the teacher, attended to all his needs and went to sleep after the teacher had gone to bed. This was the concept of serving the teacher.

This manner of service helps the student to be in tune with the teacher. You come to know the person and his preferences when you live with a person, serve him, and attend to him. What happens is that slowly, the student’s preferences are also in step with the teacher’s preferences. It is not easy to serve somebody. Service is a process of slowly letting go of the ego. This is where the identification between them takes place. In any good relationship, there is identification. When you see the relationship between a husband and wife, you can see the devotion that exists between them.

When you admire somebody, you automatically imbibe those qualities. Here, as the student admires the teacher and serves him in the spirit of worship, he automatically imbibes many of the good qualities of the teacher, and his own likes and dislikes are offered up in the process. In order for him to serve the teacher, he must become agreeable, favorable, and compatible with the teacher and so his own preferences, likes and dislikes are let go in the process. This is how the services or seva enables the student or disciple to grow to be in tune with the teacher.

As the Vivekacūḍāmaṇi says:

तमाराध्य गुरुं भक्त्या प्रह्वप्रश्रयसेवनैः ।

प्रसन्नं तमनुप्राप्य पृच्छेज्ज्ञातव्यमात्मनः ॥ ३४ ॥

tamārādhya guruṃ bhaktyā prahvapraśrayasevanaiḥ |

prasannaṃ tamanuprāpya pṛcchejjñātavyamātmanaḥ || Vivekacūḍāmaṇi, 34 ||

Having worshiped with devotion that teacher – the one who has studied the śāstras, who does not have pāpa, who is not affected by desires, who is a knower of brahman, who is calm like the fire that does not have any more fuel, who is an ocean of compassion without any reason, who is a helpful friend to the seekers who salute him with appreciation – one must approach him who is pleased by the service (done to him) with a proper attitude and ask him as to what is to be known about oneself [Vivekacūḍāmaṇi, 34].

May you serve your teacher at the level of body, speech, and the mind. May you perform actions serving the teacher at the physical level, at the level of speech and that of the mind, worshiping the teacher. In the 13th chapter, Lord Krishna says, ācāryopāsanam, meditate upon the teacher, serve and worship the teacher through your acts, words and thoughts. Prasannaū tamanuprāpya, the teacher becomes pleased with the student. When he is pleased, he is favorable; he has been won over by you. Therefore, win them over, make them happy, please them.

Surrender carefully

One important thing about surrendering to the teacher is that the teacher should be a person who has no need for your surrender. Ideally, serving the teacher would be most fruitful when the teacher has no need for service. He has no need for being served, he does not need any favors, and he has no agenda as far as the student is concerned. He does not want anything from the student. He has no agenda for the student as far as his own personal needs are concerned. It is the student who is offering himself.

It is the best way of offering because there is no risk of being exploited. Otherwise, you can be exploited. Surrendering must be done very carefully. Feel your way through it. Slowly, learn about the person and let the teacher also learn about you. That is why we say it is a process. It is not something that happens overnight, although, if it happens overnight, it is fine. It may happen. All of this is ultimately also determined by your past karma; it is quite possible that you will meet a teacher and find that he is the right one for you. Normally, however, when an initial reverence is created in you, it will take some time before the śraddhā and bhakti are developed to the point that there is a tuning up with the teacher, and the teacher is pleased with you.

Paripraśna

The third stage is paripraśnena, asking the question. When you find that the teacher is pleased with you, you ask the question. The teacher is pleased, not as much with your service as with your sincerity and devotion. He finds in you, a worthy student who is sincere and desirous of knowledge. Prasannaū tamanuprāpya, when you find them pleased with you. Pścchejjṣātavyamātmanaḥ, you should ask the question that you want to know. Paripraśnena, ask. This is when the questions are asked.

A guru answers the student, not the question

A question shows that there is a desire to know, and that one has been deliberating. For a question to arise we must have been deliberating upon it, working at it. It shows the person’s sincerity, the value the knowledge holds for him, and his desire to know. That is how the question becomes important. Otherwise, the teacher is going to say, tat tvam asi, because that is the answer to all the questions. Very often, we find that the Upaniṣads open with questions; the Kenopaniḥad opens with a question, and the Mundakopaniḥad and the Kaṣhopaniḥad are both based on questions asked by the students. We find that this truth is unfolded differently in different Upaniṣads, because each deals with a different question depending upon the background and orientation of the student. The questions are different according to what the student has been deliberating upon.

The question reveals the questioner. The teacher answers the questioner, rather than the question. Often, we may not necessarily be able to articulate what our feelings are, but still ask a question. The teacher who answers the question should know where the question is coming from. This is what we mean when we say that the question reveals the questioner. Then the ground is set for the upadeśa or teaching.

Qualifications of the teacher

The first of this verse describes the qualification of the student, and the second line describes the qualification of the teacher. Lord Krishna says, jṣāninastattvadarśinaḥ upadekḥyanti te jṣānaṁ, the wise and learned teachers will definitely impart knowledge to you. Jṣāni means learned and tattvadarśi means wise. The teacher is referred to in the plural, out of reverence. If an earnest student comes to him, it almost becomes the duty of the teacher to give him the knowledge. He is not obliged to do so, but he will because the teacher is always very compassionate. ‘Ahetukadayāsinduḥ bandurānamatām satām’, the guru is an ocean of compassion for no reason, and a friend to the pure who perform obeisance to him (Vivekacūḍāmaṇi, 35). Thus, the guru is the very friend and caretaker of those who approach him with sincerity.

This verse from the Bhagavadgītā describes the process of establishing a relationship with the teacher and creating favorable conditions so that he is enthused, motivated and inspired to teach. When the right combination is there, the knowledge will definitely take place.