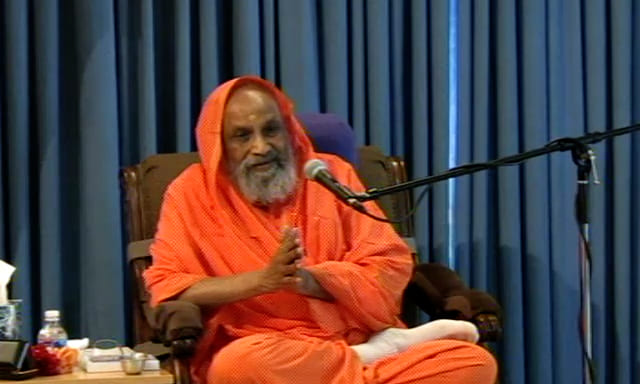

Swami Dayananda Saraswati

Excerpt from the forthcoming Tattvabodha, Arsha Vidya Research and Publications, 2009

What is vairāgya?

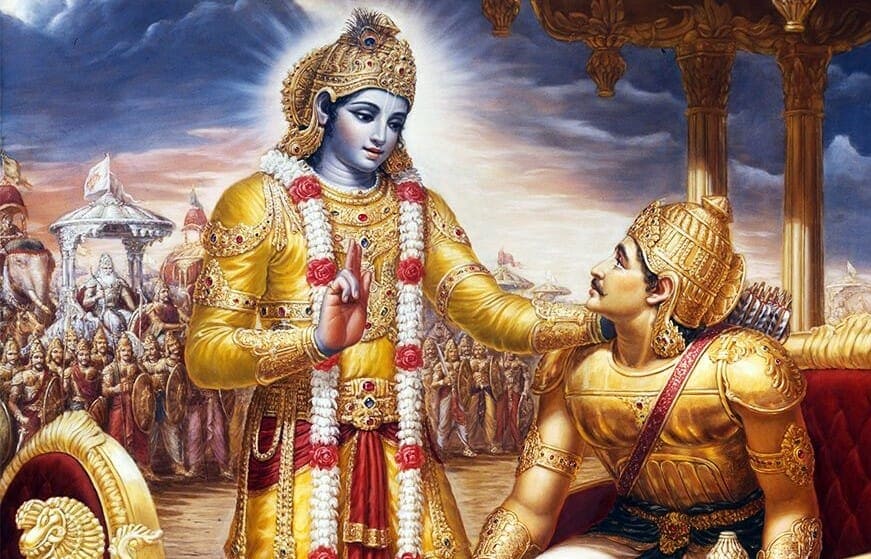

This is a very important thing. We have to see it properly. Virāga is the absence of rāga, which is a longing. The word ‘rāga’ lends its own meaning to a simple desire. It implies that you see something that is not there. And what you see is something fascinating. In reality, there is nothing there to fascinate. A desire for food is real. Hunger is real; empirically, it is real. So the desire for eating is real, and culturally we have come to know that certain things are edible. Modern nutritionists have also confirmed it. Before nutrition, as a subject matter, came into the picture, people were eating and surviving. People ask me, ‘Swamiji, how do you know that they survived?’ Because you are here, and that is enough. Therefore, they were surviving by eating food that is culturally given to us. Traditionally, it has been coming down to us, and we also add a little bit now and then. Now, this food is real, and I want food, and it is a real desire. This is one thing; there is objectivity here.

Then what is vairāgya? Let us consider money. That is real. Who says money is not real? If anybody says money is not real, then let him give it to me! You can’t say money is not real; it has a buying power. As long as it has got currency, is not demonetized, then it is money. If they withdraw the buying power completely, it is only colored paper. So, this is money; it has a buying power. This is real. Now, if you say that money will solve the problem of your insecurity, that is what we call a value superimposed upon the object. This superimposition, which we will discover in much more detail later, is of two types. When you mistake an object for something else, that is a superimposition. Or, if you don’t mistake an object for something else, but add a value to the object which is not there at all, that is also a superimposition. If you take it to be more valuable than it is, that is a lack of objectivity. I think that is the lack of vairāgya. Therefore, what does vairāgya mean? Objectivity, maximum objectivity. That means that the least subjective value is added to the various things with which you are connected in your life. Understand that everything has its objective value, and if you give it more than that, it is lacking in vairāgya. If you hold on to something that makes no sense, that can be because of a ‘savior psychology’. You want somebody to save you, because you feel that you are finished. That is an old problem, because the need to be saved by somebody is itself due to a self devaluation. That is the problem. And if somebody comes and says, “I will save you, don’t worry,” that means you are devalued forever. Therefore, this savior-seeking, this hope that somebody is going to save you, has layers of superimposed values. Nobody is going to save you, nobody can save you, and nobody needs to save you; that is the beauty of this vision. Nobody needs to save you because you are saved. Whether you think that somebody is going to save you, or some money is going to save you, or some situation is going to save you, you are adding value to something which, unfortunately, it doesn’t have. This is lack of objectivity, otherwise called lack of vairāgya.

If you think that heaven is going to save you, that is a mistake. It is definitely not going to save you. But it will save us. How? Because once you have gone to heaven, we are saved from you. That is the only relief in this. In heaven, also, if you have gone there as an individual, you are going to be an individual there and will have all the problems of the individual. This is emphasized here because unless this concept of heaven gets out of our heads, we are not going to think properly. We will always be in the clouds, and beyond the clouds, as heaven is beyond the clouds. Please understand that this is clouded thinking. So the author of the Tattvabodha says here that vairāgya is iha-svarga-bhogeṣu icchārāhityam, absence of desire with reference to all those promised enjoyments and pleasures here, and in heaven. That can be total, I tell you. Here it may not be total, but definitely there it can be total. We need not have a desire for that because it is all silly. Heaven may be there, or may not be there, and even if it is there, so what? It is a holiday and you will come back again, so it is not worth pursuing. That kind of a dispassion towards heaven and heavenly enjoyments and promises is vairāgya.

Many religions will fall by the wayside because of this understanding. They can get hold of you only if you are interested in heaven. We are not at all interested in such heavens. If someone wants to go to heaven, let him pursue that. We don’t want non thinking people. They create more problems. Therefore svargabhogeṣu icchārāhityam, absence of desire for enjoyments promised in heaven is required here. Suppose someone says that you will be in love with God in heaven. Why not now? I can be in love with god right now. If he says, “Not here. Only there,” why? What is the logic for that? Love is an emotion we have now, here; it is not a heavenly emotion. It is something that we know now, so why not love god now? These illogical ideas we have to forget.

Now, what else? Iha-bhoga, enjoyments here. Suppose someone says, “Swamiji, I am not interested in heavenly enjoyments.” Thank god, you said it. “You are talking to me as though I am interested in heaven, but I am not interested. If I were interested, why should I come to you here for these classes? If I wanted to go to heaven I would have become a ‘born-again’, I would not have come here. I am here because I am interested in what is here,” iha bhogeṣu iccha. There can be a desire for enjoyment here, but again, these desires have to be understood. They can be binding or non binding. If they are non binding, you have dispassion, vairāgya. If they are binding then we have to make them non binding. A binding desire is one towards which you have the sense, “Without this, my life is empty.” That is lack of objectivity. Therefore, only when towards every pursuit there is a certain objectivity is your mind available for mokṣa. When the viveka is there, then vairāgya will also be there. Then life itself becomes yoga. Marriage, etc., becomes yoga, as do all pursuits, because there is objectivity. Greater objectivity means a greater commitment to mokṣa, because viveka and vairāgya go together.

Vairāgya is a word that is generally not understood properly. It is commonly thought that vairāgya means turning away from everything. But, you know, when you turn away from everything, you carry it all in your head. Whatever you turn away from will always catch you; it travels with you. But when you are in the midst of things, and you discover a certain objectivity, this is dispassion born of dispassionate thinking. There is less subjectivity which means that you do not superimpose values, which are our own creation, on things, which they do not have. Even a relationship, like marriage, etc., can help you only when you are objective. If you marry for the sake of marriage, as an end, then the marriage will end! Marriage cannot be an end because if it is, it is an ideal, and there is no ideal marriage at all. Marriage is not an end; it is a means where both partners help each other to gain the end. Then it becomes yoga; it is a means for an end. In Indian marriages we have a seven step ritual, saptapadi, in which the couple walk together towards a common goal as friends. Therefore, there is no bad marriage at all, if it is a means. If it is an end, there is no good marriage at all. This is what we call objectivity. Vairāgya is not running away from everything. I don’t believe in it, and I don’t encourage it. It is silly and it doesn’t work. Marriage, and all that we do, is a means for an end, mokṣa. This is the virāga, dispassion, in ihāmutrārtha-phalabhoga-virāgaḥ. We will discover all this more and more. As we proceed, these things will repeat themselves in all the texts, so every time we will get something else, not totally different, but something more.