Swami Dayananda Saraswati

Excerpt from the forthcoming Tattvabodha, Arsha Vidya Research and Publications, 2009

What is this discrimination of nitya-anitya, what is not subject to time, and what is nityānitya-vastu-viveka? This is what we call puruṣārtha-vivekaḥ. A puruṣārtha is what is desired by a person. Though a person desires different things, all these are reduced to a few in this inquiry. The pursuit of security through money, etc., is reduced to artha, and the pursuit of pleasures, in various forms, is reduced to one, kāma. So we have artha and kāma. Then there is a pursuit of dharma. Dharma for one’s own growth has a value in its own right. Andcdharma is also puṇya, gaining some grace by which I can attain something here or in the hereafter that is a more conducive situation, one in which I will be more happy than I am now. This is also dharma. All religious pursuits of all religious people, of different religions, come under dharma. So dharma, artha and kāma are called puruṣārthas.

Now, let us consider security, artha. We ask the question: Are we really seeking security or are we seeking freedom from insecurity? It is a very important question. Who wants crutches, tell me? The person who cannot stand on his own legs. As long as one is insecure on one’s legs, one wants crutches, one needs crutches. Therefore the one who is insecure needs crutches, and the one who is secure, doesn’t. Crutches are not a part of your outfit. You don’t dress up nicely and don some crutches also. No, people need crutches only when they feel insecure on their own legs. So, the more you need crutches, the more insecure you feel.

You tell me now, do you want crutches or do you want freedom from insecurity? Nobody wants crutches. And there are many crutches. Finances are crutches, name is a crutch, fame is a crutch, power is a crutch, community is a crutch. You want to become a member of a community so that you will feel good. That is why all cults will tell you, “You are special.” This is nothing but politics. Somebody is keeping you under their control by telling you that you are someone special, and that it is you against many. So you become special because you belong to this elite group. Who told you it is elite? This is how all these cults function. And they proselytize to others also, to bring them into the group. Whoever comes and tells you that you will become special when you join their group, you should be careful of. In fact, keep away from that person; that is better. If I say the same thing, “Oh, you are special because you have come to this,” then you should be careful of me, also. I do say, though, that you have come here because of some puṇya, some grace, because you are seeing through all these cults. These are all crutches.

When you seek any type of security that means you feel insecure. There is nothing wrong or right here. We are only trying to understand what is going on. Therefore, we are not making any judgment that this person is right, and that one is wrong. Right and wrong is not the point. What we are trying to get at here is: what is the situation? The situation is that one feels insecure about oneself. Being self conscious, the human being is insecure. And there are definitely reasons for his sense of insecurity, all of which all valid, according to the person.

Therefore, we are going to analyze all these reasons, which seem to be very valid. We are going to question their validity and invalidate them. How? Not simply by saying that they are not valid, but by seeing thoroughly the fallacy of all the arguments behind them. Thereby, they all fall apart, because they don’t have a standing. And as they fall apart, naturally the insecurity also goes away along with them. The reasons that support the sense of insecurity are seen as not valid at all. And when you see the fallacy of the reasoning which supports the sense of insecurity, then there is no reason for insecurity. That is analysis and that is the discrimination here.

It is important to understand that I am not seeking security. I can’t stand being insecure, and that means I am seeking freedom from insecurity. When I seek freedom from insecurity, should I seek security or should I question why I am insecure? Which is correct, tell me? When I seek security, I am taking myself for granted as someone who is insecure. This is taking oneself for granted. When I begin seeking security, I have already concluded that I am insecure. Now, how real is this conclusion? What are the reasons for this conclusion? All those things we analyze. That is the viveka here. Am I really insecure, or is something else insecure which I take to be myself, and then feel Insecure.

If I, ātman, is the body, definitely ātman is insecure because the body is insecure. It is subject to every passing microbe. It is subject to age, to time, and therefore, is going to join the majority one day. I know this very well, and therefore, I am insecure. Any way I look at this body, it is insecure, so, naturally, if ātman is as good as the body, then it is not good at all. If it is as good as the body, it is subject to time, aging and illness, and therefore, I am insecure. If the truth is that I am not insecure, then there is confusion. If there is confusion, I require an enquiry which will resolve it. Because there is confusion, that inquiry has to be called viveka, not just vicāra, which also means enquiry. Viveka is enquiry, but enquiry wherein there is confusion, where two things are mixed up.

Security is what we mean by the puruṣārtha of artha, but security is not really the puruṣārtha. It is freedom from insecurity. What does that mean? Mokṣa, freedom from insecurity is the puruṣārtha. Now you can understand what mokṣa is. It is not one of the puruṣārthas. Generally they say that there are four puruṣārthas—dharma, artha, kāma, mokṣa—and among them, mokṣa is the best, caturvidānām puruṣārthānām madhye mokṣa eva parama-puruṣārthaḥ. This is all childish. Another person can say that is your opinion. If there are four types of fruit, one person can say, “This is the best,” but another can say, “That is for you, sir. You choose jackfruit, but I can’t stand the smell of it, so you’d better take it.” Who is to decide what is best? In fact, when they say that mokṣa is the best, the idea is freedom from seeking. That is called puruṣārtha. Here we are discussing freedom from seeking security, artha. Now, between artha and mokṣa, how many puruṣārthas do you have? Tell me. Suppose you are seeking artha and another person is seeking mokṣa. Do you have two puruṣārthas here? No, the two are reduced to one, mokṣa.

Then again, let us look at this other puruṣārtha, kāma, seeking pleasure. Pleasure is any conducive situation in which I can tap some happiness for myself. What does that mean? I am unhappy, so naturally I seek happiness. But it is not the happiness that I want; I want to be a happy person. Happiness is not an object. If there is an object called happiness in the world, then we all can make a beeline towards it, and all of us can get a little bit of happiness. Just as we all go to the gas station and ask for so many gallons or liters of gas, we can go to this particular station called, ‘happy station’ and ask the attendant, “Give me two units of happiness.” There is no such object in the world. Therefore, you can’t seek happiness. Then what are you seeking? You are seeking a happy person, not happiness. If you are seeking happiness as an object, everybody will be seeking that. But one person goes to the beach, and another leaves the beach. One person is going to the mountaintop, another is coming down. Does that mean he has had enough of happiness? The one going up is in a hurry and the one coming down is also in a hurry. Watch the streets and you will find the traffic going both ways. One person is going that way to find happiness and someone else is coming away from there. All of them are going in different directions. What does it mean? From this it is clear that nobody seeks happiness, because it is neither in the East or in the West, or in the North or in the South, or up or below. All that each one wants is to see the happy self And to see the happy self, does he have to go to the mountaintop or come down, or go to the beach or leave the beach? My god, you want to see that fellow, yourself, the happy self. Where is he? “I don’t know, maybe there on the mountain top or on the beach I will come across the fellow.” All the time you are seeking the happy self.

When you are seeking the happy self, what do you have now? I may not say it is an unhappy self, but a not happy self; that is better. You may not be positively unhappy now, but occasionally positively unhappy, and otherwise not happy. So saying that you are not happy now will include being unhappy. Unhappy may not include not happy, however, so the not happy self is what obtains now. “I am not a happy self” is the conclusion. Therefore, are you seeking the happy self or are you seeking freedom from the not happy self’? If you are seeking freedom from the not happy self, how many puruṣārthas do we have here? Kāma and mokṣa? Freedom is mokṣa. Freedom from the not happy self, freedom from the insecure self is what I am seeking. There is no artha that I am seeking, there is no kāma that I am seeking. What is this? We start with artha and kāma and afterward, we end up in mokṣa. Then there is someone who says, “I want to go to heaven, and therefore, I want puṇya.” This heaven is the end for a lot of people in the world. They are waiting to go to heaven, and if you say to such a person, “You want to go to heaven? Let us go today,” he will say, “No, no, no, not today.” Why? Because he is not sure about heaven. So he wants to live his life. Suppose a heaven such as the one you are thinking of is available. What do you want there? “Here I am imperfect and I have to be saved. I will be saved in heaven.” Again he seeks freedom from the same thing—being insecure, unhappy, alone. It is the same thing. “There I will feel secure and happy, that is my hope, and though I am imperfect, I will be saved from sin.” What he wants is freedom from this conclusion, “I am imperfect, I am a sinner.”

This is dharma, so now we have dharma, artha and kāma. The pursuit of growth is also dharma. But even as a grown up person, I will have legitimate anger, legitimate problems, and therefore, be legitimately insecure, unhappy, etc. Even the grown up person is also a limited person. Because he also thinks that he is the body, all the limitations beginning with, “I am a mortal” will not go away. Therefore, whatever I am seeking in the grown up person, I see the limitations of that. And nobody wants to be the limited person. Whether you are seeking puṇya-pāpa, or growth, or anything else, that seeking is because of a conclusion, and that conclusion we question here. It is that sense arising from the conclusion that you want to be free from.

If I am imperfect and I want to be free from imperfection, what will I do? They translate sthita-prajṅa as ‘man of perfection’. I don’t know where they got this idea, which has misled a lot of people. What does ‘man of perfection’ mean? How should his nose be, how should his eyes be? Should he be able to see all around, not only in front, but behind? And will he see the microbes also? That means he will have no peace; when he breathes in, he will see the microbes going in, so he can’t breathe happily, this man of perfection. The word ‘perfection’ should be taken out of our dictionary. There is no such thing as perfection. Everything is perfect because there is a reason for everything to be what it is. The mosquito is perfect. When he bites you, he is more perfect. And when you slap him, you are also perfect, and that your hand is dirty is perfect too. It is an all cause-effect relationship—perfect. The concept of perfection is a problem. Who is to decide what is perfection? And ‘man of perfection’ as a translation for sthita-prajṅa, is in common usage. What about ‘woman of perfection’, why only ‘man of perfection’? It is all a problem. The idea that I am imperfect is the problem. Are you? Do you want to be perfect or do you want to be free from being imperfect? If I am imperfect, how will I become perfect, tell me? My nose is imperfect, so what do I do to make it perfect? Making what makes me perfect, if I am imperfect? Nothing will make this person perfect. Even if he goes to heaven, it is the imperfect person going to heaven, so he is bound to be disappointed. He will look around and find, “Oh, there is no cricket here.” If he is a European, “There is no soccer here.” The point is, wherever the imperfect person goes, he will find imperfection.

Therefore, I am not seeking perfection; that is ridiculous. I am seeking freedom from imperfection. Now, how many puruṣārthas do we have? Only one. Except for dharma as growth, which can be a puruṣārtha, everything else, on analysis, is not a puruṣārtha. In the pursuit of artha you discover your growth, in the pursuit of your kāma, you discover your growth, so only self-growth can be a puruṣārtha, a relative puruṣārtha, nothing else, really speaking. And that is also not going to be the puruṣārtha because, there again, I will see myself as imperfect. Therefore, freedom from imperfection is the puruṣārtha, freedom from insecurity is the puruṣārtha, freedom from being unhappy is the puruṣārtha. So how many puruṣārthas do we have? Only one puruṣārtha. And this is sought after by all. Who is not seeking this? But there is no discernment, viveka, of that. Even though everybody is seeking that mokṣa, people do not know that they are seeking mokṣa. It is very clear. And so, there is confusion.

The fallacy in the conclusion that I am insecure is not discerned. That I am seeking freedom from insecurity is not discerned, and therefore, I seek security. That I am seeking freedom from being unhappy is not discerned, and therefore, I seek myself, as the happy person, by manipulating the world or manipulating the mind. Somebody manipulates the mind, somebody manipulates the world—both of them are saàsārins. A yogi tries to manipulate the mind, but in fact, the mind manipulates him, because his wanting to manipulate the mind is dictated by the very mind. The mind makes him manipulate the mind, really. What I want you to understand is that the one who wants to manipulate the mind and the one who wants to manipulate the world are both saàsārins, because they are both trying to ‘become’. ‘I am unhappy’ is the conclusion from which I want to become free–it is freedom that I am seeking. Whether a conclusion is true or not true, freedom is what I am seeking. And therefore, it is very clear that there is a lack of discrimination.

If I think that in heaven I can solve the problem, as though there is a problem right now and it cannot be solved, that is also the lack of discrimination. Even in heaven the problem is not going to be solved, because if you go to heaven, you are going to be there as an individual, different from everyone else, so it will be the same thing. Suppose, for the time being (we will analyze this later), we accept that god is in heaven. All the faithful people go up to heaven and are sitting around god. Where will you sit? Where is your position? Somebody has to occupy the first row, and somebody has to occupy the second row. I have some logic for this. They say that you should go two hours early to the airport to catch your flight. If all of us go two hours early, all of us have to stand in the queue, so I will be last in the queue and go one and a half hours later. The only problem is that everybody concludes the same thing. But people do go two hours before, so I can go half an hour early and be the last person. In heaven, however, somebody has to be there in the front row, somebody has to be in the second row, and somebody has got to be in the third row. Which row are you going to be in? And god is sitting there. We are all looking at god. And then, right in front of you is a basketball player. That means you can’t see the lord, unless you crane your neck this way and that. It is the same problem that we have here. All right, suppose you have seen the lord. Just understand all this. Unless you laugh at it all, these erroneous conclusions won’t go away from you. So then, you have seen god enough and start to wonder, “How does his back look?” God’s back must be different from other backs, you know, so now you have to see the back of god. It is the same problem. And you can’t see it, because to see you have to get up and walk over all these people. Therefore, what do you do instead? You look around to see who else has come. And you see this fellow who you know was a bootlegger, a drug pusher, and had committed all the crimes in the book—and not in the book. This fellow somehow made it to heaven by some last-minute confession or whatever. So he has to come to heaven, and when you look at him, you become sad right in front of god. Why? “Had I known, I would have done a few things when I was down below that I had wanted to do. Anything I liked was considered immoral or illegal.” So right in front of god you are sad. Just because you are there. There is no other reason. God is not to blame. Heaven is not to blame. You have gone there and that is enough.

Suppose you think that you will lose your individuality in heaven. That means individuality can be lost. If so, you don’t need to go to heaven for that, you can do that here, now. What can be lost alone can be lost. And what can be lost is not real; it is what we call anitya. What can be lost is anitya, what is, is nitya. Therefore, dharma, artha, kāma, are for only one puruṣārtha, mokṣa. This is called viveka.

What is not going to be produced. What I want is to be free from all this, so by a process of change I am not going to become the happy person, the secure person, the perfect person. The imperfect person cannot become perfect by a process of change. What is imperfect will continue to be imperfect, no matter how many changes are brought in. You can embellish a broomstick with any amount of ornamentation, but still, it is a broom stick. Please understand this. The problem remains. Why not solve the problem? That means understanding that the process of becoming itself is anitya . Anything that becomes is subject to becoming, and that new condition is subject to become something else. The old status is gone, the new status is gained, only to go away and again be replaced by a new status, and again, a new status, and again, a new status. This continues. And even if you get a new birth—let us extend it further—again you will find yourself with the same problem. This is the process of becoming an anitya, so, no matter what you do, you are not going to accomplish what you want to be nāsti akṛtaḥ krtena.

Therefore, if there is really a solution, it is not within the sphere of becoming. And if I have to solve the problem without becoming, that means the solution should be me. That is called nitya. I can say that I don’t know what that nitya is, but this much I know—nitya cannot be produced. What is eternal cannot be produced. This is why an eternal heaven does not exist at all. If it exists, it should be me, right now. That is eternal heaven. If it is me, and I cannot see that it is me, the problem is due to what? Ignorance. This is called viveka—nityānitya-vastu viveka.

What is this nityānitya-vastu-viveka? Anitya means finite, time bound, and we have seen that everything is anitya. Whatever comes in time, is lost in time. The individual who undergoes a change, undergoes further change. This change, even if it is in the form of a new human body, or any body, will also undergo change. It is a matter of belief, but still, we accommodate that. Even if I gain another physical body, whether it is a human body or a celestial body, whatever be the body, and whatever be the place, that will also undergo change, because it is all time bound. The important thing to understand from this is that in becoming I become an eternal seeker. The one who wants to change will be eternally seeking a change, and another change, and another change, then afterwards another change, and then afterwards another change. We can go on repeating this. This is eternal seeking. From the very seeking itself, from the constancy of the seeking, we understand that we are not trying to accomplish something finite. We want to accomplish something that is free from being finite. Therefore, we are seeking what is eternal. We are not seeking what is non-eternal, but what we are doing will only result in what is non-eternal. Any change is, again, only for the finite being, so even a heavenly abode is not going to really make a difference. And that is what is said here.

We can understand that everything in this world, and even a heavenly world, is anitya. Therefore something eternal is not going to be created by anything, nāsti akṛtaḥ kṛtena. If at all there is something eternal, it is not going to be created, it is not going to come in time. So it should already be here. And further, if what is eternal is other than the seeker, the non eternal, changing person who is time bound, that will not be eternal. So if there is such a thing as something eternal, it has got to be the very nature of the seeker. Later we will discover that, but now we have established that I am not seeking what is non eternal anymore; what I am seeking is freedom from seeking. And the freedom from seeking should be centered on myself. Here, if one is a little more informed about the tradition, he can even name what he wants: nityam vastu ekam brahma. This is the advantage of the Vedic background. The Veda tells us that there is one vastu, one reality, and it is ekam, one, and non-dual, and its name is brahman. So what is indicated by the word brahman is nitya, and that alone is nitya.

Therefore, what should I seek now? I should seek brahman which is nityam vastu. And everything else other than that Brahman, whatever we seek, he says is anitya, tat vyatiriktam sarvam anityam. Tat vyatiriktam here is other than that Brahman. Heaven is abrahma, because it is not nitya; it begins at a given time. The concept of an eternal heaven is childish. There is no such thing. If heaven is something that begins at a given time, it will be lost in time too, and therefore, is non eternal. All that you seek locally is also non eternal, it is very clear. That is why you have to be careful. When you earn some money you have to be very careful in your spending, otherwise, it will be lost. It will not last eternally. So in everything you have to be careful, because everything is non eternal, finite, not only in terms of time but in degrees, in its quality, in its capacity to make you happy, secure, etc. It is all found wanting. Therefore, anything that I seek, which is within time, is going to be non eternal. Really, what I am seeking is freedom from this seeking itself.

This is mokṣa, and if that is what I am seeking, then I should seek Brahman, which is eternal. And being eternal, Brahman cannot be a product of your karma. You cannot produce Brahman. Once it is said by the śāstra that it is eternal, nityam brahma, it is not going to be produced. If it is not produced then it must be existent. If it is existent, it cannot be existent as other than myself. For, if it is other than myself, it will become time bound, that is, it will exist in time and space. If it exists in time and space, it is non eternal. If it does not exist in time and space then it can only be myself. These are all conjectures now, but we will be looking at all this thoroughly. So, there is one vastu, called Brahman, and that is nityam vastu. This is the Vedic information we have, and with this Vedic information we know that what we are seeking is eternal, and it is Brahman, which is one, and it is in terms of knowing. This much knowledge one must have, nityaà vastu ekam brahma. And everything other than that Brahman is not eternal, tadvyatiriktam sarvam anityam. This is callled nityānitya-vastu-vivekaḥ.

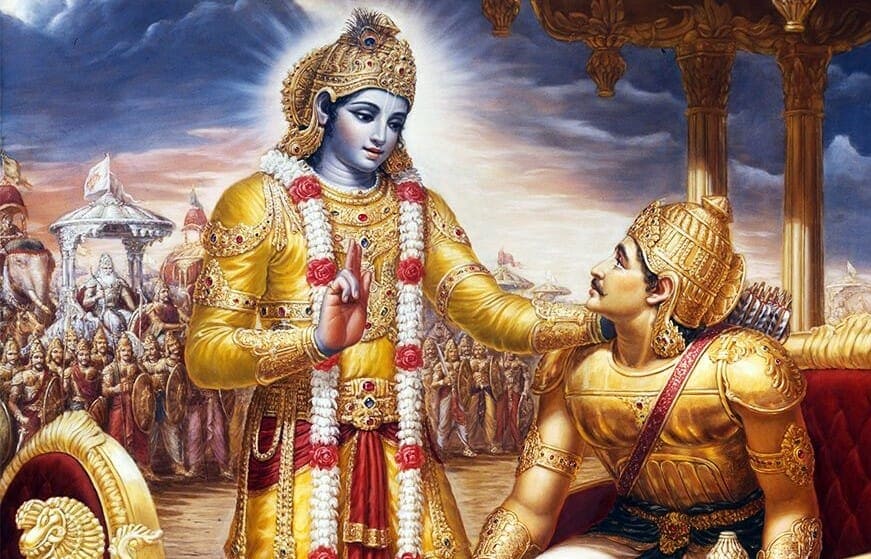

Brahman is still not known. We are only talking about qualifications here. Brahman is not known, but there is something to be known, which is Brahman. That level of understanding is what is called viveka. What is the viveka here? It is assimilating the human experiences, and from there, extending our logic, our reasoning, to also cover the experiences one may gain after death in another incarnation. Whether it is here or elsewhere, heaven or anything, it is all going to be finite. I, the saàsārén, the becoming person, will continue to become; there is no solution to this. What I am seeking is not available in the sphere of seeking. This kind of understanding is viveka. And being born and brought up in the Vedic culture, a person can even say, “What I want is Brahman.” Only then can you go and ask the teacher, “Please teach me what Brahman is,” how the upaniṣad is. And for that, he must have knowledge of what he is seeking. You can’t desire a thing which is totally unknown to you. The person here who goes and asks the guru, the teacher, knows where to go and seek, and also knows what to seek, adhéhi bhagavo brahmeti. This is Bhṛgu, the son of Varuṇa who was a great learned person, a wise man. Bhṛgu had never cared to ask his father this knowledge, but one day he went to him and asked. One day he realized he should ask this. That means he had gone through life experiences, assimilated them, and said, “O.K. I have had enough; now let me understand Brahman.” Then he goes to Varuṇa–bhṛgurvai vāruṇiḥ, varuṇam pitaramupasasāra. He approached his father and asked, adhéhi bhagavo brahmeti, “Bhagavan, please teach me what Brahman is.” That means he knows that he has to gain Brahman, and that the gain is in terms of knowledge. You know, if you have to gain something which is eternal, then it cannot be a product of your action, karma-phala. Why? Because karma is finite; it is done in time.

Any action, including prayer, is done in time, and therefore, it and its result are finite. This is what is very important to know. Prayer is also an action; you must know that. And that is why it is available for choice. You can pray this way and you can pray in another way, because prayer is an action. You can pray in different forms. We allow that. But, the result is not going to be the end that we are really seeking. That is where people commit mistakes. All religions talk about prayers and say that prayers will produce results. And in this we have no problem whatsoever, in the sense that we validate every form of prayer. Whether it is a Hebrew prayer or it is in Latin or Sanskrit, it is all the same. Therefore, you can say that all prayers are efficacious. But we must know that it doesn’t mean all religions lead to the same goal. The goal of prayer is only a finite result, because prayer being finite, the result also will be finite. We also want finite results. Eating produces finite results. That is why in the morning you eat, and again, at lunch time you eat, and in the evening you eat. So this goes on. Then, after some years, you find that while at first you were eating, later, what is eaten is eating you! Therefore, eating produces a finite result. But that doesn’t mean that you don’t eat. The breathing process is also finite. For a length of time it will go on, and one day it will stop. That doesn’t mean I stop it. It will stop; why should I stop it?

What we need to understand here is that prayer has a finite result. There is confusion about this all over the world. Prayers have their results, and they are finite in nature. If that is so, then whatever be the karma, action, that you do, even if it is a sophisticated prayer, the result of that karma, is finite. If it is finite, then I can’t seek my freedom from this becoming. The becoming process is anitya, and therefore, I cannot free myself from this process of becoming called saàsāra, by gaining a particular result, because that will be lost. Then again I have to become; this goes on.

Therefore, there is only one way of gaining what is nitya, eternal. What is eternal cannot be a product of a change, karma. It should already be existent, and it should not be separate from me either. If it is separate from me, then I have to gain it. If I have to gain it, it will be lost, because it will be gained in time. Therefore, it has got to be myself alone, as we will see clearly. If it is myself, then it is a matter of knowing. This much viveka one should have. That is why the introduction to this topic is so big. This much viveka one must have; it is not that suddenly you start Vedanta. This whole process must be very clear—that it has got to be myself alone, and if it is myself, then I am separate from it purely by ignorance. And therefore, to dispel that ignorance, I need to know, I need tattva-viveka. That is why the author of the Tattvabodha said, “I will explain the method for discerning the truth, which is the means for mokṣa,” mokṣa-sādhana-bhūtaà tattva-viveka – prakāraà vakṣyāmaḥ . This much discrimination, understanding, one must have. Therefore, what I am seeking is not elsewhere. We need to know this, because people take to a spiritual pursuit not knowing what it means. Everybody has something to offer. One person will say, “This is not my path; this is not my cup of tea.”

“Oh, What is your cup of tea?”

“It is not the usual tea; it is herbal tea.” They call it herbal tea, as though black tea is not herbal. It is also herbal. Who told you black tea is not herbal? In this way, each one has his own cup of tea. This is what they call ‘spiritual shopping’. You go around shopping as though it is available for shopping. This is all due to the problem not being clear.

You have no choice in knowing. If you want to see a color, you have to use your eyes; what choice do you have? You can’t use your nose. That is not fanaticism, either. Where there are options, there can be fanaticism. If one holds on to some particular thing, excluding all others without valid reason, that is fanaticism. Fanaticism is holding on to a non verifiable belief, like, “If you follow me, you will go to heaven; otherwise you will go to hell.” In this, heaven is a non verifiable belief, that I will survive death is a non verifiable belief, that by following this person I will go to heaven is, again, a non verifiable belief. And having gone to heaven that I will enjoy it is another non verifiable belief; that otherwise I will go to hell, is a non verifiable belief; that hell is very hot is a non verifiable belief; and that I will not enjoy it, is another non verifiable belief. That I will not be able to air condition my room there is a non verifiable belief. All these are non verifiable beliefs. A non verifiable belief can be totally wrong. If it can be, or is proven to be totally wrong, but still you say that it is right, that is fanaticism. Another fellow comes and says, “I am the latest and the last. Don’t follow the previous fellows; god has changed his ideas. This is the new message. All of the previous ones were only prophets. There were no messiahs, only prophets, and I am the latest prophet. God had been talking to me in my dreams, and this is what he said.” And he tells you, “Follow me and you will go to heaven.” Now, tell me who is right and who is wrong in this? How can anyone prove who is right and who is wrong? The belief itself is non verifiable, so how am I going to prove that this fellow is right and the other fellow is wrong? Or the other fellow is right, and this fellow is wrong? Perhaps both can be right. Suppose both of them turn up in heaven—”Hey, you also came?” Or, both of them may be wrong. And even if they are right, I have another thing to say. I am not interested in that heaven, because it is saàsāra. Understand that. That is the thing we are talking about. They are fanatics. When they are not sure and they promote it, or when there are options, and they talk about one thing as the only option, or hold on to a non verifiable belief system saying that it is the thing, because somebody said so, that is fanaticism. That somebody, again, you have to believe, along with everything else. This is fanaticism.

But here, what we are saying is that you are the solution for the problem that you are. Nobody else, nothing else, no heaven, can be the solution. Even if you go to heaven you have to discover yourself. You need not have to discover it only here. In heaven you may have a chance to discover it, perhaps. The śāstra says that also. There is a special heaven for that. There are seven heavens: bhuḥ, bhuvaḥ, suvaḥ, mahaḥ, janaḥ, tapaḥ and satyam; and if you go to the seventh heaven, there, perhaps, you will be taught. Taught what? You are the solution. “That’s what I was told when I was down below. Why should I come here for this?” This has to be understood, and such understanding is called nityānityavastu-vivekaḥ. I have no option whatsoever. I have to know. This is not fanaticism; it is knowledge. It is knowing what I am, which is entirely different from believing what I would be. Believing what you would be is entirely different from knowing what you are. And knowing what you are is freedom from seeking, and you see that right now, here. Therefore, mokṣa is the end and it is in the form of self knowledge. This is what we call viveka.

This viveka also implies a certain discipline in your thinking. This is the cognitive ability, the intellectual discipline. In olden days, in India, when Vedanta was taught they would make sure the student had studied Sanskrit grammar, because that requires logic. Sanskrit language, presented through a meta-language in the Pāninian system, is logical. You have to open those grammar sutras. And it is only by logic that you can understand what is being said there. So by study of grammar one develops acumen, and also, by study of the discipline of logic. There is a special śāstra for that, the nyāya-śāstra, which they study in order to be skillful in reasoning. Intellectual discipline is what helps you discover fallacies in reasoning. Dispassionate reasoning is essential, because otherwise, you will succumb to emotional logic, and nobody should succumb to that. Therefore, dispassionate reasoning, without being cantankerous, but at the same time seeing the fallacies in thinking, is a must. For us, this capacity is a must, and therefore, intellectual discipline is also included in viveka. Discriminative enquiry implies cognitive skills. In modern times, we assume that modern education must have given you the intellectual discipline you require for this. Otherwise I would first have to teach you nyāya, then later we would start Vedanta. The assumption is that having gone through the study of exact disciplines like physics, mathematics, etc., you will have the required acumen. Unlike history, where there is no logic in thinking, these exact disciplines give us a certain capacity to think properly. That is also included in viveka.

When the viveka is there, then what will you have? You become more objective. This is called dispassion, vairāgya.