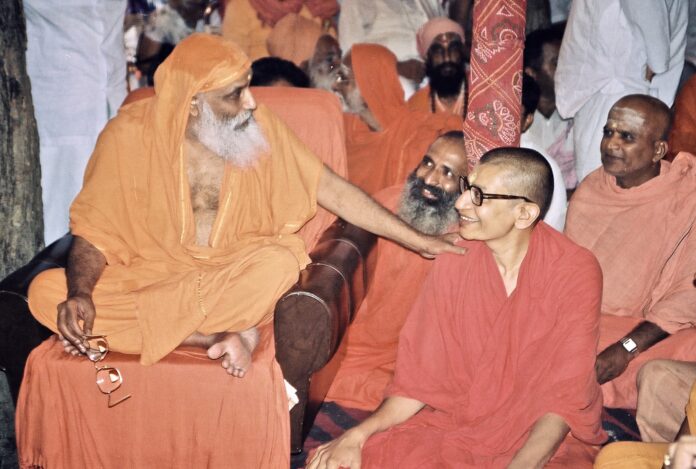

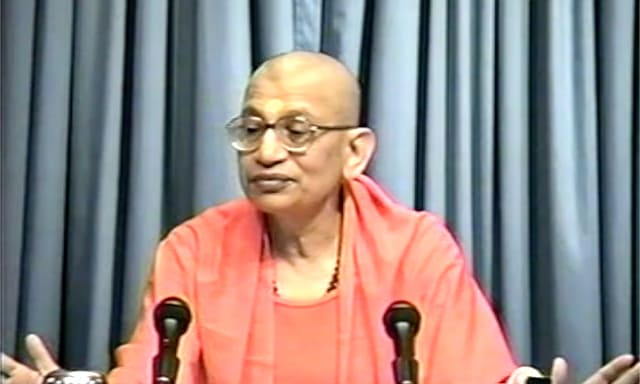

Swami Viditatmananda Saraswati

Excerpts from the book, Satsanga with Swami Viditatmananda, Volume 1.

In the prakaraṇa text Dṛk-dṛśya-viveka, a verse occurs, teaching viveka or discrimination between dṛk, the subject and dṛśya, the object:

asti bhāti priyaṁ rūpaṁ nāma cetyaṁśapañcakam

ādyatrayaṁ brahmarūpaṁ jagadrūpaṁ tato dvayam

The group of five constituents, “Exists, shines, attractive, form and name” pertain to all dealings in the world. The triad of the first three is the nature of brahman and the pair of remaining two is that of the world [Dṛk-dṛśya-viveka 20]. In our lives there is a mixing up of the subject and the object. The text teaches us how we can recognize the object as the object and the subject as the subject. While talking about the truth of the universe, the author draws our attention to the fact that everything in the universe has five aspects. Everything has a name (nāma), and there is a form (rūpa) corresponding to the name. Further, the thing is. It exists (asti). How do I say that a thing is or that it exists? I know it because it is an object of my awareness (bhāti). If it were not an object of my awareness, I would not know that it exists. If I ask you whether I have horns on my head you will say that I don’t, because you do not see them or because you are not aware of them. Thus, existence and awareness (asti and bhāti) go together.

The author also adds that everything in this universe is lovable, and has attractiveness (priyam). There is love for existence and there is love for consciousness, and therefore there is love everywhere. Or let us say that everything has the capacity to be an object of love. Love and joy always go together. I love that which is a source of joy. I naturally dislike that which is a source of unhappiness or pain. So both love and joy go together, which means that there is joy or happiness everywhere. Therefore, we have asti bhāti priyam, existence, shining and joy associated with every object, every name and form.

“But Swamiji, I do not see happiness everywhere. I see happiness in a few things but not in other things”.

The reason why I do not see happiness in a given object can be either because happiness is not there or because my mind is not tuned in to see that it is there. Because of rāga-dveñas (likes and dislikes) in my mind I have preconceived notions about where happiness is and where it is not, what happiness is and what it is not. If these preconceived notions are dropped, and if my mind is open and free of any demand as to how a thing should be, there will be no difficulty in appreciating happiness everywhere.

The Taittirīya Upaniñad says:

ānando brahmeti vyajānāt, ānandādhyeva khalvimāni bhūtāni jāyante, ānandena

jātāni jīvanti, ānandaṁ prayantyabhisaṁviśantīti.

He knew ānanda as brahman; for from ānanda indeed, all these beings originate; having been born, they are sustained by ānanda; they move towards and merge in ānanda [Taittirīya Upaniñad, 3-6].

This passage says that all beings are born of ānanda, happiness, are sustained by ānanda, and ultimately merge back into ānanda, to become one with it. This is like saying that all pots are born of clay, are sustained by clay and go back to become one with clay. All pots are nothing but clay. Similarly, when it is said that everything is born of ānanda, is sustained by ānanda and goes back to become one with ānanda, it means that even now, everything is ānanda. Thus, from what the Taittirīya Upaniñad says, everything is nothing but the manifestation of ānanda.

How is it that I do not see ānanda, happiness everywhere or feel it? Is it because it is not there? Some people insist that they can accept something only when they see it or experience it. But just because we do not see or experience something does not mean it is not there. In case of seeing, I may have a problem with my eyes, some defect in my eyes, and therefore I do not see it. So even if something is there, I may not see it. If I remove that defect in my eyes then I can see. Similarly, the mind is the instrument with which we experience happiness, and if we do not experience happiness it may not necessarily be because it is not there. Maybe my mind needs some tuning up. There is some problem in the mind, and it needs to be removed. The problem with the mind is the presence of various likes and dislikes, the rāga-dveñas, attachments and aversions. When they are removed the mind becomes accepting, non demanding. Whenever I am non-demanding and am able to respect and accept a thing or a being as it is, I find that I enjoy it, whether it is a flower, a tree, a river, a lake, a dog, a person or anything else. If I make a demand that it be different from what it is, I cannot enjoy it.

Asti means that a thing is. Bhāti means that it shines in my knowledge. Priyam means it is attractive. This is the truth that obtains in every name and form. The attractiveness part is not always clear to us. It is not always experienced. That ‘a thing is’, is an experience. That ‘it shines’, is also an experience. But to experience attractiveness, I am required to give up my demand, or preconceived notion of what ‘attractiveness’ is. If I think that attractiveness is only in a certain kind of a nose or a certain kind of eyes, I can see it only there and not elsewhere. But if I drop all my definitions of what attractiveness is, I can see it everywhere, because it is everywhere. Happiness or love is everywhere. Everything has a potential capacity to make me happy. What I need to do is to invoke or explore that potential.

Every object is unique in that it has its own name and form. This means that every name and form is different from every other, but every object also has universality, in that everything is asti bhāti priyam. Let us look again into the example of the pot. There is something that distinguishes one pot from the other, and that is its unique name and form or shape. But there is something universal in all the pots, namely clay. Similarly, in this world, there is something that separates each object or being from another, and this is, its particular name and form. On the other hand, there is also something that is universal, and this is asti bhāti priyam.

What is the relationship between the clay and the pot? The clay is the truth of the pot. In fact, what we call pot is nothing but the clay. The pot has no existence apart from the clay and therefore the pot is nothing but clay. Similarly, if asti bhāti priyam is the universal aspect of all objects, what does it mean? It means that the truth of all objects is nothing but asti bhāti priyam! This means that even when I perceive an object as a particular name and form, its underlying reality is asti bhāti priyam. If I try to determine the truth of an object by progressively sub-dividing it into its building blocks, it seems to disappear, leaving nothing. But that is not so. We say that something does remain. What is it? The one who is investigating is the one who remains!

Similarly, where is the asti bhāti priyam which is associated with every name and form? Is it out there? No. It is the nature of the very subject who asks this question! With reference to the subject, the asti bhāti priyam (it is, it shines, it is dear) which is in the third person, will get transformed into the first person. It will be asmi bhāmi priyam (I am, I Shine, I am dear) instead. We have changed the case. To begin with, we recognize that the essence of everything is asti bhāti priyam or saccidānanda (existence, awareness, fullness). Then we recognize that saccidānanda is indeed myself.

A text called Advaita Makaranda opens with the verse:

ahamasmi sadā bhāmi kadācinnāhamapriyaḥ,

brahmaivāhamataḥ siddhaṁ saccidānanda-lakñaṇam.

Always I am. Always I shine. Never am I an object of dislike to myself. Therefore it is established that I am brahman which is of the nature of existence, awareness, and fullness [Advaita Makaranda, 2].

I never dislike myself. I may dislike other things, but as far as my love for myself is concerned, it is unconditional love. My love for other things is always conditional. But I never hate myself. I always love myself regardless of where I am or how I am, whether I am good or bad, rejected or accepted. Therefore where is this asti bhāti priyam? It is in fact nothing but my own Self. If asti bhāti priyam is my nature, and we say that all that there is, is asti bhāti priyam, what am I looking at? My own Self! What, then, is this creation? It is nothing but a manifestation of my own Self.

pūrṇamadaḥ pūrṇamidaṁ pūrṇāt pūrṇamudacyate.

This creation is complete, and that Self is also complete because this completeness arises from that completeness [śānti mantra from Yajur Veda]. The Self is pūrṇam or complete. This creation is also pūrṇam or complete because this creation has emerged from the Self. Therefore, recognize this pūrṇatvam, the completeness. Recognize that every name and form is in reality asti bhāti priyam and that asti bhāti priyam is the very nature of mySelf. Then pūrṇam or completeness alone remains. There is no duality. It is one without a second. Asti bhāti priyam is all that remains.